The Myth of Nostalgia Culture

Or towards a general theory of drugstore magazine racks.

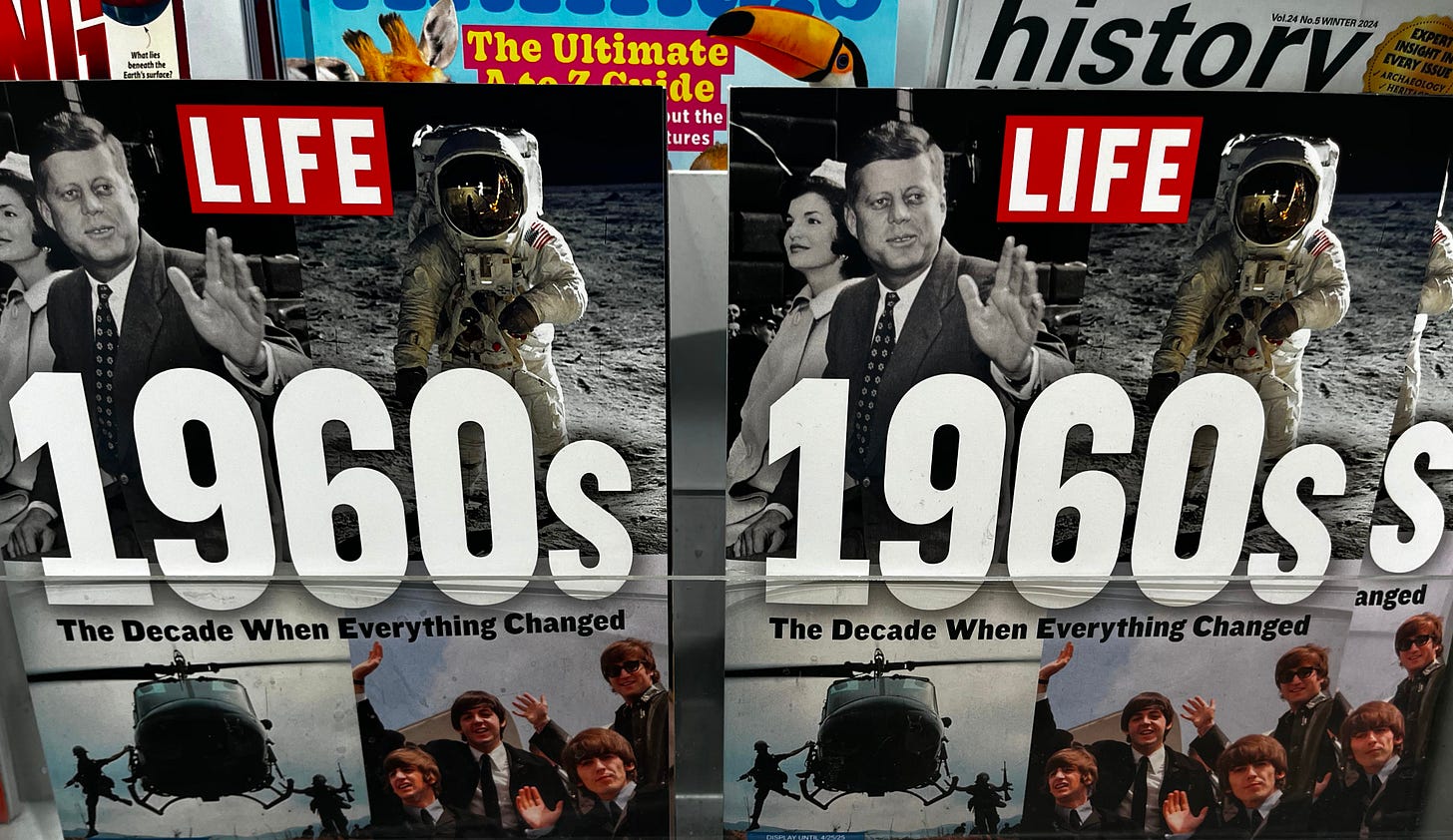

If you’re a regular listener of my podcast, you’ll know I’m persistently irritated by the magazine stands you often see near the checkout at the likes of supermarkets and drugstores. I’m sure most of you know exactly what I’m talking about. Think cover stories about Frank Sinatra or longform retrospectives with titles like “The Many Lives of Jackie Kennedy” in which instances of the word “Camelot” could easily be turned into a lethal drinking game. At my local Shopper’s Drug Mart, every date on the calendar is somehow the anniversary of the first time the Beatles appeared on Ed Sullivan; the day we are collectively remembering the Moon landing; the occasion for a 7000th wistful remembrance of some episode or incident that probably made an appearance in the movie Forest Gump etc etc. (Ok, I’m exaggerating here. But only very slightly.)

This kind of thing is, of course, merely one expression of a much wider phenomenon.

In culture today we are incessantly confronted by objects, images, and idioms rooted in the past. Both movie theatres and streaming platforms, to take the most obvious example, have for years been stuffed with sequels and reboots — so much so that anything original increasingly feels like the exception. The findings contained here, in a post by Stephen Follows, are quite old at this point but give a good general picture of the trajectory (which, I think it can be safely assumed, has only intensified since he compiled them). Quoting directly, here are a few:

In the past 10 years (Follows was writing this in 2015) the number of top grossing films which were sequels has more than doubled.

In both 2013 and 2014, seven of the top 10 grossing films were either sequels or prequels.

Almost half of all the money spent on Adventure and Action films in the past decade has gone to sequels or prequels.

These findings are significant, not just because they so neatly illustrate the extent to which we’re now living in a culture of sequels, prequels, and reboots, but because they also seem to suggest that the phenomenon is driven by moviegoers themselves. Which is to say: if studios are now pumping this stuff out so much, it’s presumably driven by some kind of organic cultural appeal or wider collective yearning for the past.

That, or so it seems to me, has become a somewhat widespread assumption. As I put it in an essay for Jacobin a few years ago, the ubiquity of reboots and recycled crossover objects has given rise to a whole discourse concerned with nostalgia, the crux of it being that contemporary mass culture is defined by an ambient craving for the old and familiar.

While this might be true in some vaguely-defined sense, it strikes me as the kind of vulgar psychological explanation we should generally try to avoid if we really want to understand things. Sweeping cultural trends and patterns most often have identifiable roots in the wider political economy of a society — even if contemporary discourse (for a variety of reasons to complex to go into here) is often congenitally predisposed not to think about them. A society as ideologically averse as our own to materialist analysis (which is to say: to the idea that social phenomena might have structural or material explanations) will invariably turn to physic, cultural, or even spiritual narratives to make up the difference.

This impulse, I think, undergirds a lot of shoddy writing and arguments. But I also think it has the very unhelpful implication of mystifying trends whose explanations are, in practice, much less ethereal. In my Jacobin essay, for example, I made what I believe is a compelling case that the ubiquity of “nostalgic” cultural products is in fact easily traceable to mass media consolidation. I won’t belabour the argument, since you can just read the essay if you’re interested, but in essence: thanks to the financialization and deregulation mania of the 1990s, a handful of corporate monopolies now own and control much of the landscape of mass entertainment and consequently churn out sequels and reboots because they’re much lower risk investments (among other things). The effect of this might be a generation of movies and shows that exude an aura of nostalgia, but the cause isn’t some deep-seated yearning to bask in old and familiar things.

The myth we live in a nostalgia culture often misses the fact it’s being served to us by a small handful of corporate monopolies as an extension of their business strategy. And thus, what appears to be an organic cultural phenomenon is actually a function of how power and resources are distributed — and maldistributed — in the cultural industry.

Which brings us back to those magazine stands, and the decidedly boomerish content contained therein. Again, it’s tempting to conclude these things simply exist because there’s a market for them (which, no doubt there is), in turn implying — in much the same way — a culture defined by some ambient craving for the old and the familiar.

I realize I’m drawing mostly on anecdata here, but in looking at these magazine racks it’s hard not to immediately think about the wider issue of Gerontocracy — by which I mean the quite observable reality that many institutions today, especially political ones, are nearly or wholly dominated by people in older age demographics. Here, we need look no further than the American political class, which by this point has more or less elevated gerontocracy to the level of performance art. It’s also illustrated quite vividly and disturbingly by the two men who faced each other in America’s 2020 presidential election (the victor in that contest being a politician who was quite literally born closer to the presidency of **Abraham Lincoln** than his own).

Again, I think it’s quite easy to ascribe a mystical narrative of one kind or another to all this that runs parallel — and in some places directly through — the nostalgia narrative I’ve elsewhere been speaking about. The far more obvious explanation, however, is that the various examples offered simply reflect the disproportionate balance of wealth, power, and resources in politics and in society at large.1

I think, more than anything, this is why those magazine racks irk me so much: they seem perfectly, almost comically, emblematic of a society where major institutions are fronted and dominated by people whose reference points are decades out of date; where cable news drives so much of political discourse despite in practice being more or less the exclusive purview of urban baby boomers; where candidates who appeal to the young (some of them, it should be said, on the older side themselves) are spurned and derided by hostile elites in favour of dishonest, morally bankrupt politicians like Joe Biden or Donald Trump; where the more conservative preferences of a particular generation2 are wildly overrepresented in many liberal democracies; where the language of politics is suffused with midcentury ideas of middle class life and the turgid idioms of the Cold War; where so little in either politics or culture ever feels original or new.

Again, I don’t think any of this is really because 21st century society is so congenitally prone to nostalgia that it reflexively looks backward. If anything, it’s because the generalized maldistribution of wealth, power, and cultural influence today have made it increasingly difficult to do anything else.

It goes without saying that I’m speaking broadly and generally here: there are plenty of younger people with power and wealth, and plenty of people over 60 who can’t pay their bills. (And, while he’s never vibed with me, there’s absolutely nothing wrong with liking Frank Sinatra!)

Thank you! It really irritates me that the assumed preferences of an amorphous public (which just so happen to line up with what major studios want to sell) are so often taken as a kind of force majeure, without any attempt to explain *why* in material terms. I mean, sure, maybe it's pure coincidence that independent movies exploded in the US after anti-trust laws severely limited the power big studios could wield over distribution. Or that the dominance of blockbusters and the return of the big studios came about right after Reagan stopped enforcing those laws in the mid-80s. Or that the increasing concentration of wealth and power since the 80s, and the increasing financialisation of media, has had some effect on what films are made and who makes them. I guess it's remotely possible some of that stuff is important - but on the other hand maybe it's all just vibes. Who's to say?

In the same way that neoliberalism supercharged and sped up dynamics that have always been part of capitalism, my sense is that the nostalgia boom of the last couple decades has been a highly concentrated version of the sense of displacement, in both time and space, that capitalism has always produced with rapid social and technological change, "annihilating space by time" (Marx) and decimating local communities and landscapes. (Your M&U conversation with Will about disenchantent and Herzog's 'Herz aus Glas' is in the back of my mind here.) There's been some interesting writing on nostalgia as an ambivalent emotion that's neither good nor bad in itself, just something humans feel and have felt especially keenly in the modern world that capitalism has wrought. That ambivalence means that it can be captured by reactionary nationalists and media corporations, but it can also be channeled into something like a "Green New Deal" which invokes left-wing, or at least social-democratic, nostalgia. (On that note, you might like Grafton Tanner's 'The Hours Have Lost Their Clock: The Politics of Nostalgia'.)

I hadn't made the explicit connection to gerontocracy, but you're right of course - Boomers refuse to release their grip on culture just as surely as their refuse to release their grip on politics. If Disney Plusaversary signals the zombification of the former, then surely Donald Trump and Joe Biden arguing about their golf handicaps signals the zombification of the latter