The Enshitification of Gaming

If you want a vision of the future, imagine being trapped inside a giant Assassin's Creed map forever

I recently listened to a podcast discussion about the early 2000s TV series Lost (2004-2010), having just watched roughly 1.5 seasons’ worth of episodes for the first time ever. The initial season, for what it’s worth, is entertaining enough. But the conversation I heard — between Matt Christman and Felix Biederman of Chapo Trap House — seemed to confirm a festering worry I was feeling after having taken in 20 episodes or so. This is a series that dangles tantalizing mysteries, large and small, right from the very beginning. Why is there a polar bear on a tropical island? Why does said island (clearly deserted) seem quite obviously not deserted? Why exactly has being in a plane crash somehow cured one of the main characters of his inability to walk? As the show unfolds, it gradually builds out an ever-more intricate structure around mysteries like this, incessantly hinting that some great revelation will eventually appear to explain it all.

The crux of Christman and Biederman’s conversation is that all of this is finally in the service of…well, nothing. Lost exists for no other reason than to keep you watching. Its curiosities, its mysteries, its byzantine storytelling, its non sequiturs, its periodic dips into magic realism serve no higher philosophical or narrative purpose. All of this is there simply to keep the audience on board, but those who traverse the show’s six seasons will find nothing waiting on the other side. Lost, then, is not actually “about” anything besides its own continuation. And as the two of them point out, this makes it an early harbinger of much that lay ahead in mass entertainment and beyond.

Today’s digital economy — encompassing news, entertainment, and much else — is fundamentally concerned with grabbing and keeping our attention. This, as Chris Hayes points out in his recent book The Siren’s Call is the foundational resource in the contemporary media environment because, unless this is successfully captured, there is nothing to be monetized. Thanks to smartphones, the proliferation of apps, and plenty of other developments, our attention is a scarce commodity that is increasingly more valuable than gold because there are now always so many different things competing for it.

The implications of this, I think, are quite radical — and they extend far beyond the things most of us intuitively understand or take as truisms about how the current digital media landscape works, e.g.: that many websites have become completely unusable thanks to ads and pop-ups; that many of the apps on our phones are now glorified slot machines with intentionally addictive systems of game-ification and reward built right in; that many of the shows we watch on Netflix — even some of the better ones — have become much, much too long; that most streaming platforms are hardwired to begin playing something new the moment a film or show has finished because they have an interest in artificially juicing their metrics (and so on).

I don’t think I’ve ever written about video games on here before. But they’re often a bellwether for wider cultural trends and, with all of this in mind, I’d like to turn to Assassin’s Creed. If you’re unfamiliar with this series, it comes by way of developer Ubisoft and, since the first instalment in 2007, has yielded more than a dozen games. Initially built on stealth (it’s right there in the title) the series has gradually morphed into something closer to action/role-playing. Even if stealth is still technically an option, the best course is generally to run straight at the enemy and button mash your way to victory rather than execute a carefully planned strategy. Every instalment has a different historical setting of some kind, and all of it is tied together with an inscrutably convoluted meta-story involving two factions waging a war across time.

In theory at least, all this should redound to something both playable and interesting. And, for what it’s worth, some of these games are genuinely fun (Assassin’s Creed Black Flag, for example, lets you fight giant sea battles in a pirate ship). But they have also become paradigmatic examples of video game bloat. Having grown up playing games on the N64 that you could now easily fit into an email attachment — Starfox, one of my favourites as a kid, was only 8 megabytes in size — and I never imagined this could be a problem. As a child, I relished finding every little secret or alternative path a game had to offer, and could wring countless hours of joy from the search. In Starfox 64, the subtlest maneuvers executed at the right time could find you meeting new characters or open up whole new levels.

I still remember the elation I felt from these discoveries, and you might think that larger games would offer them in greater abundance by definition.

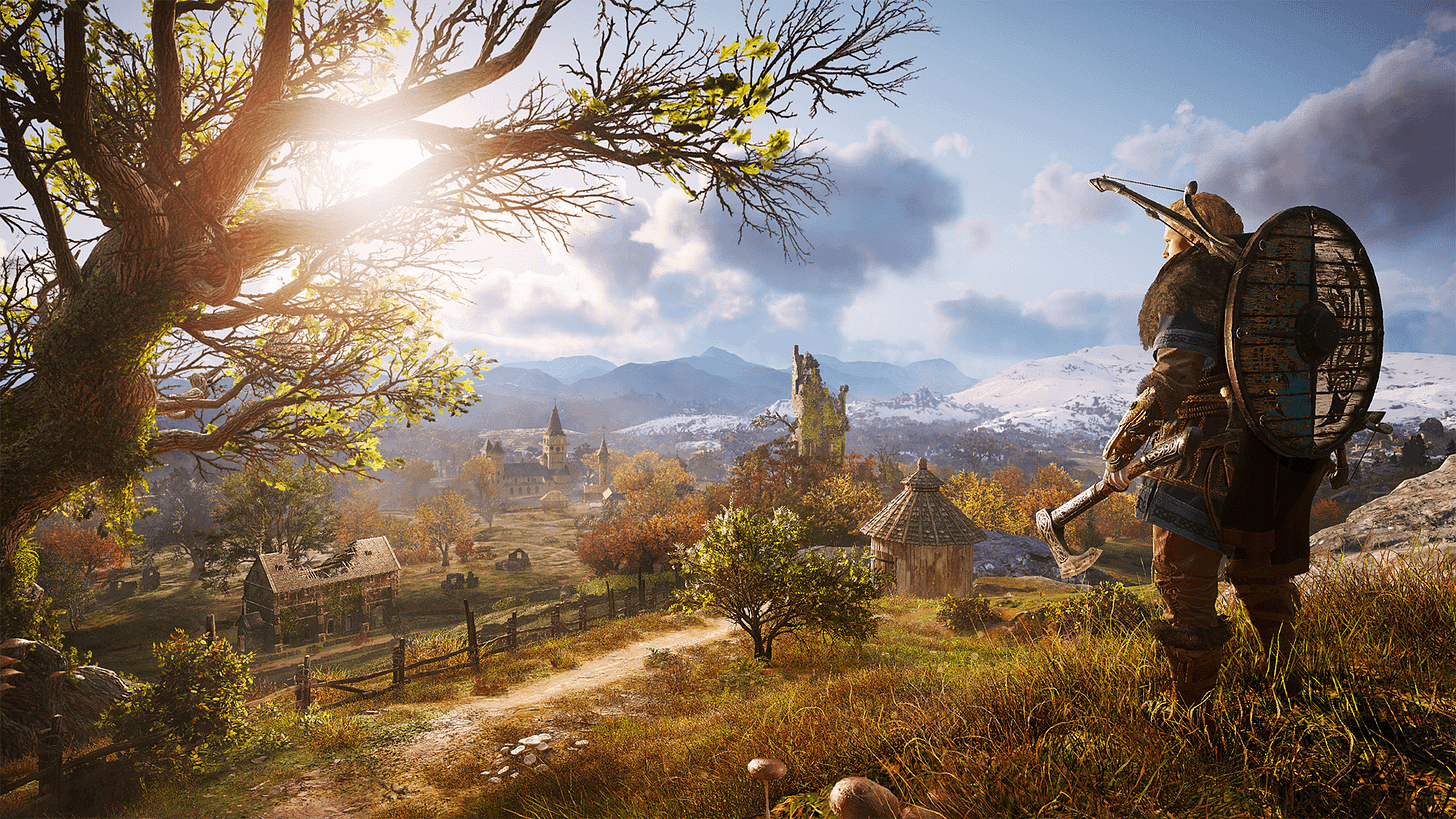

The likes of Assassin’s Creed Odyssey and Assassin’s Creed Valhalla are proof positive this isn’t necessarily true. Both offer huge, beautifully-rendered worlds: the former being set in Ancient Greece, and the latter mostly in 9th century England. I found the first few hours of Valhalla so promising I couldn’t figure out why it had been the target of criticism upon release. There was, it seemed, so much to do and so much to explore. There are all kinds of weapons to choose from, and a massive skill tree to constantly level up. If you get through the main game, there are also several expansions probably worth a dozen or so hours apiece, and thus several more maps dotted with settlements to raid, quests to fulfill, intrigues to become entangled in and so on.

But play enough of Valhalla and you begin to realize there is actually no point to any of this. Its massive map might be dense with tasks, artifacts, and secondary characters — generally indicated with little icons that make the world less immersive — but it is also fundamentally empty. Here, size and intricacy serve no higher purpose (narrative or otherwise) and even the potentially fertile terrain of Norse mythology often gets short thrift. Instead, all of the game’s quests and map markers finally add up to an arbitrary string of tasks punctuated with little incentives that are there for no other reason than to coax the player into carrying on. A massive skill tree is there so you can level up but, since the game also constantly upscales the stats of your enemies, you experience level 75 or 150 much like you experience level 1. Even the beautiful environments and landscapes don’t keep things interesting when you’re being asked to do the same kinds of things over and over again.1

You might reasonably ask what exactly a gaming studio gets out of designing its virtual world like this. Well, having charged people $60 or so bucks for a game, many developers will now create a parallel system of micro-transactions that encourages players to spend real world money on upgrades for their characters, many of which are purely cosmetic. They want you to keep playing less out of enjoyment than because doing so holds your attention and, in turn, offers them new opportunities to monetize it.

In fact, the very act of buying a game now often means something quite different than it used to. Once upon a time, a game was something tangible, physical, and self-contained. Today, the same purchase feels more akin to securing a licensing agreement that grants access rather than ownership. And, thanks to online integration, a game is now essentially open-ended and can theoretically be expanded with additional content in perpetuity.

This, quite obviously, represents a genuine evolution in certain cases, because a good game can now be supplemented with a self-contained story or new questline without the need for a full-blown sequel. Far more often, though, it simply mirrors the broader trend in mass entertainment wherein everything is a franchise and nothing is allowed to just exist for its own sake.

All this gets at a deeper issue with the attention economy, because it indicates a problem far greater than what’s suggested by web pages dotted with popups or Netflix dramas allowed to age beyond their best-before dates. There is a point at which substance/content becomes entirely subordinate to form, and much of the modern digital landscape is a bleak testament to what that ultimately means: vast virtual worlds with nothing in them and a 100+ hour checklist worth of repetitive tasks to perform; news and opinion websites that are really content mills that exist mainly to stimulate the ideological pleasure centres of their audiences; the proliferation of derivative, recycled narratives and mass entertainment that would rather reproduce the same parochial constellation of franchises again and again and again than take a risk on creating anything new.

Which finally brings things back to what irks me so much about Assassin’s Creed Valhalla. If I were writing a traditional review, I would probably complain that the game becomes boring very quickly; that nothing about its gameplay even comes close to justifying its size; that its combat is crude and clunky; that it doesn’t take proper advantage of its source material, and so on. But after giving up on the game, I realized that what I disliked the most was the extent to which playing it resembled the experience of being caught in any other repetitive and mindlessly-addictive digital activity.

In the attention economy, it seems, even a viking power fantasy set in 9th century England can be made to feel like scrolling.

So as not to sound too jaundiced here, there are obviously gigantic games being made today that do justify their size and scope. Here, Ubisoft’s efforts with Assassin’s Creed feel somewhat like the evil twins of FromSoft games like Sekiro and Elden Ring, or Rockstar’s Red Dead Redemption, which I have played twice all the way through.

This is why I only play indie games (and Nintendo) at this point. Amazing, original games are still being made, just not by any of the big studios. Same goes for movies.

Yeah, the videogame industry has been on a weird spot the last decade and a half.

The console generation that got me into gaming was the PS3 / XBOX 360 era, because it had the game originality of the previous generation, with the technology of the next generation, a perfect sweetspot between the real and digital world, wich a lot of people have nostalgia today of the culture of the early 2000's.

What scares me is, what kind of new bussiness model big developers will create to get more money in the future? if games are designed purposefully to waste the people who play them, how is a game in the next decade gonna look like? i dont think that the philosophy of "fun first" is gonna be on their list.

Seeing how big developers are now pivoting to downscaling games, i think we will head into an era of free to play games, with a lot of less content, with a lot of even more predatory monetization (even wilder that we have today, or even, a whole new system created from scratch like a new version of the battlepasses of today, or lootboxes).

But well, a man can dream of a better world...