The centre (right) will not hold

The left, not centrism or moderate conservatism, is our best and only firewall against the extreme right

Last September, former British prime minister Gordon Brown published an op-ed in The Guardian bemoaning several recent instances of would-be European moderates capitulating or attempting to appease the extreme right. Brown’s argument speaks to something both real and alarming: namely, the extent to which many European conservatives (and supposed liberals like Emmanuel Macron) are now reorienting themselves — particularly around the issue of immigration. Brown’s op-ed also offered a sobering survey of recent far right momentum, from Italy and France to Austria and Holland.

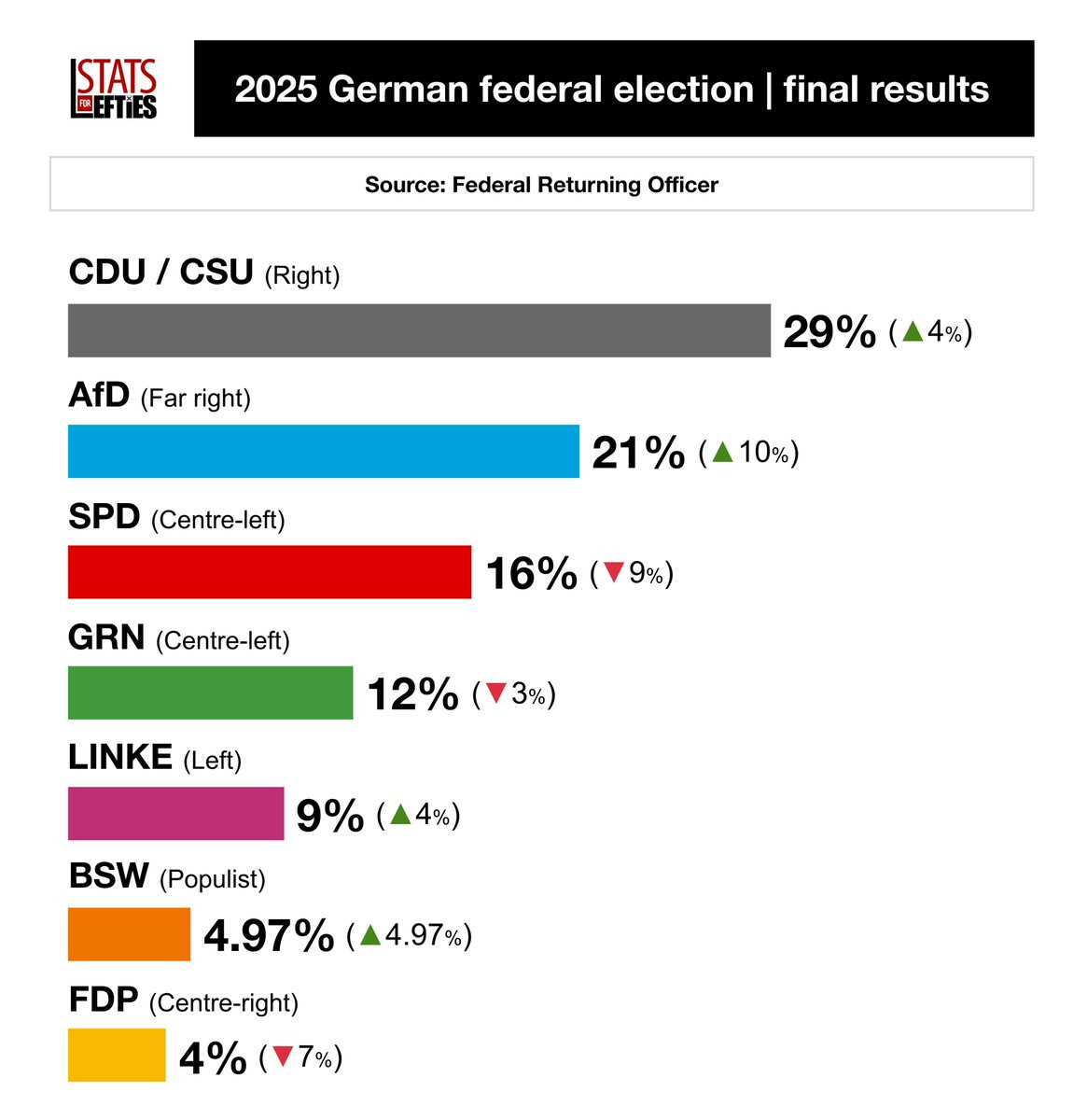

To his examples we can now add a further one. In this weekend’s German federal election, the Alternative for Germany (AfD) — extreme even by the standards of the European far right — achieved its greatest success to date, securing just over 20 percent of the vote and finishing second overall behind the Christian Democratic Party (CDU).

The thrust of Brown’s argument — that appeasement by so-called moderates has only boosted the extreme right — is particularly applicable in the German context. The CDU, led by now incoming Chancellor Friedrich Merz, pivoted hard to the right on immigration, as did Olaf Scholz’s SPD. Writing in The Guardian several days ago, Berlin-based columnist Fatma Aydemir summed up the atmosphere this way:

Almost all the political parties have been busy for weeks fighting a phantom called the criminal immigrant, whom they all promise to deport or “re-migrate”, depending on the respective party’s language – or they will make sure the criminal immigrant doesn’t get here in the first place by levering out the asylum law…Sadly, almost all German political parties over recent weeks have been engaged in a race to claim that they will deport the most asylum seekers in the name of law and order. The chancellor, Olaf Scholz, of the Social Democrats, has already increased the amount of deportations by 70% in just over three years, a fact he proudly reminded voters of during the so-called “chancellor duel” TV debate. Scholz’s opponent and potential successor, the Christian Democrat Friedrich Merz, wants to go a step further and prevent asylum seekers from entering the country, while expatriating people with dual citizenship who commit a crime.

If this approach was intended to weaken the AfD it can be safely be called a failure. The CDU, despite its victory, received its second worst result ever, while the Social Democrats haven’t fared this badly since the dominant figure in German politics was quite literally Otto Von Bismarck. The CDU and SPD will now form a coalition of the centre, possibly joined by the Greens. But Merz’s decision earlier this month to pass a non-binding resolution on border policy with the aid of AfD votes — breaking with the longstanding postwar taboo among German parties not to collaborate with the extreme right — can only be taken as further evidence of its increasing success.

The only silver lining in these results, such as it is, is the surprising recovery of the left wing Die Linke — which won Berlin and beat the AfD among voters 18-24. At just under 9 percent, Die Linke’s result is in many ways a modest one (even taking into account the lower vote shares that often emerge from a proportional multiparty system like Germany’s.) Still, it’s a major breakthrough for a party that looked to be on its last legs only a few short months ago. Encouragingly, Die Linke struck an explicitly anti-fascist pose, running an energetic campaign that emphasized both bread and butter cost of living issues and took the CDU to task over its game of footsies with the AfD.

In what quickly became a viral speech, Die Linke lead candidate Heidi Reichinnek used a January speech in the Bundestag to denounce Merz and the CDU for their acceptance of AfD support, among other things declaring: “Only two days after we commemorated the liberation of Auschwitz here [in parliament] … you are working with those who carry on the same ideology.” (You can watch the speech for yourself below — as a non-German speaker, I was able to follow it with the aid of YouTube’s auto-translation feature, which you’ll find with the Settings button in the bottom right of the video).

With all this in mind, I’d like now to return to Brown’s op-ed, which becomes a lot less convincing in its second half. Having provided a lengthy list of recent outrages and far right successes, Brown proceeds to offer us a few counter-examples with the aim of showing that its forward march is not inevitable. One of them — the re-election of Ursula von der Leyen as president of the European Commission, by an executive rather than a popular body no less — is simply bizarre. I don’t feel well informed enough to comment on his Polish or Spanish examples, but for reasons that are very likely partisan Brown also includes the victory of the Labour Party under Keir Starmer in last summer’s British general election (which, having pivoted hard to the right itself on the issue of immigration, is now either trailing the far right Reform party or just slightly ahead of it depending on which poll you look at).

Much of this feels like pretty thin gruel. But, more to the point, Brown’s condemnation of “the insidious surrender of the centre to far-right prejudice” doesn’t see fit to mention the left at all. In France, where he himself begins the story, it was a broad front coalition consisting of La France Insoumise, the Socialist Party, the Ecologists, the French Communist Party, and others which held back the far right National Rally. In his own country, it’s the much-abused left of the Labour Party and other left wing forces outside of it (including the Greens and various independents) that have most strongly resisted Farage-ism and the appeasement strategy he rightly criticizes.

This blind spot in the story renders Brown’s case somewhat rudderless by the end, leaving him to again censure moderates and call somewhat intangibly for a renewed progressive agenda that emphasizes “jobs, standards of living, fairness and bridging the morally indefensible gap between rich and poor.” Insofar as such an agenda exists in tangible form, it has not meaningfully been offered by most parties of the nominal centre, centre left, and centre right for many years. Where it has been taken up by parties or politicians of the left, it’s been actively combatted by much of the nominal mainstream — which in some places has applied the cordon sanitaire principle as strongly (or even more strongly) to the left than to the extreme right.

Again and again, this approach has been a disaster. A decade plus of condemnatory op-eds and entreaties to conservative moderates have not arrested the progress of Nigel Farage, Donald Trump, Marine Le Pen, or their equivalents elsewhere; the AfD has reached its zenith while the long dominant formations of postwar German politics are at their nadir. In France, Emmanuel Macron preferred a hard right prime minister over one from the left coalition that triumphed in last summer’s legislative election. In Britain, where the already unpopular Starmer government is continuing its contemptible journey to the right, Reform looks poised to become a significant force at Westminster. In the United States, Democrats are spinning their wheels while Bernie Sanders continues to barnstorm red states and rally huge crowds against Trump’s agenda.

Gordon Brown and others in the same camp are correct to underscore the urgency of maintaining and strengthening a democratic firewall against the extreme right.

Neither centrists nor moderate conservatives are going to provide us with one.

great piece Luke

I like your writing , Luke. However the notion that it’s far right to want to alter Europe’s ruinous immigration policies of the past 30 years is about as far left as I can imagine. And Gordon Brown is no moderate