Some books I read this year, Part II

NOTE: Until the end of the year I’m offering 50% off annual subscriptions. Click here to subscribe at the discounted rate.

I’m not usually one to do lists, but the end of the year feels like a good occasion for it. I tend to read first thing in the morning, before I exercise and before I start looking at screens. Over the holiday break, I look forward to reading without the constraints imposed by work — and without, for a few weeks at least, the irritating feeling that I need to turn whatever I happen to be reading into Substack content. And speaking which: following on from Part I, here are a few more books I enjoyed in 2025.

The Acquisitive Society, by R.H. Tawney (1920)

As far as I can tell, R.H. Tawney is a mostly forgotten figure these days and, though I’d consider myself fairly well versed in the British socialist tradition, I don’t recall hearing his name until a few years ago. Tawney (1880-1962) was a Christian socialist once prolific in a number of different areas. I have yet to read Religion and the Rise of Capitalism (1926), which established him as one of Britain’s preeminent historians, but The Acquisitive Society has now firmly planted itself in my brain.

Those who have followed my writing over the past few years will have detected my growing preoccupation with what might loosely be called the problem of commodification. More and more, I have been thinking about what it really means for a society to reconstitute itself along market lines. Socialists, of course, have been talking about that in one way or another for as long as socialism has existed. But I’m convinced we are now experiencing a radicalized version of it quite unique to the 21st century: one that transcends the merely economic and penetrates society and culture like never before. This is a complicated thing to interpret and explore, but more than a hundred years ago Tawney was doing something very similar in his own time.

Thanks, I suspect, to his Christianity Tawney developed a powerful, humanist language with which to criticize the capitalism of the early 20th century. In the acquisitive society, he wrote, the individual becomes “the centre of his own universe” and moral principles are “dissolved…into a choice of expediences.” The market ethos, in turn, flattens any distinction between “different types of economic activity and sources of wealth, between enterprise and avarice, energy and unscrupulous greed, property which is legitimate and property which is theft, the just enjoyment of the fruits of labour and the idle parasitism of birth or fortune…”. “Under the impulse of such ideas,’’ Tawney writes…

…people do not become religious or wise or artistic; for religion and wisdom and art imply the acceptance of limitations. But they become powerful and rich. They inherit the earth and change the face of nature, if they do not possess their own souls; and they have that appearance of freedom which consists in the absence of obstacles between opportunities for self-advancement and those whom birth or wealth or talent or good fortune has placed in a position to seize them.

Some books are simply enjoyed, but discovering this one felt closer to a revelation.

The Third Reich Trilogy, by Richard Evans (2003-2008)

Evans’ trilogy is probably the only history of Nazi Germany you’ll ever need to read. Having devoured the first volume back in January, I soon made my way through its successors The Third Reich in Power and The Third Reich at War as well and have since turned to Evans’ two other works about the Nazis (Hitler’s People and The Third Reich in History and Memory). This stretch of 20th century history is obviously quite well known, but Evans engages it in a compelling style lush with both analysis and detail. The first volume, which effectively begins in the 19th century, was my personal favourite — in part because it’s as much about the Weimar period, with the Nazis themselves mostly in the background. The second, which begins with a fascinating chapter on the internal Nazi purge of July 1934 (the so-called “Night of the Long Knives”), narrates with terrifying detail the extent of Hitler’s takeover of German civil society — right down to bowling leagues and hunting clubs — and the patchwork of inspiring, if largely disorganized, resistance to his rule. The Third Reich At War is also fascinating, though for obvious reasons Evans spends much of his time chronicling a seemingly endless list of atrocities before we finally arrive at the regime’s collapse.

There is so much to say about these books that they may occasion a post of their own at some point in the future. But this really is history at its finest, and I may well go through the trilogy again in 2026.

All Quiet on the Western Front, by Erich Maria Remarque (1929)

All Quiet on the Western Front is one of those books that’s so famous you never actually get around to reading it. But, after watching the film adaptation that swept the Oscars a few years ago — fantastic, though also one of the single most gruesome films I’ve ever seen — I finally decided to read the novel. And I’m glad I did, because Remarque writes about war and nationalism with a vividness beyond anything it’s possible to do onscreen.

Remarque, for those who don’t know, was a German veteran of the First World War. When the Nazis took power in the early 1930s, his novel about life in the trenches was among the first they denounced as “denigrate” and took to burning in public. Even before the Nazi seizure of power, in fact, Remarque’s account of the war was considered heretical by the country’s more traditional conservatives and others who refused to abandon its myths. In 1914, Germany (along with every major power in Europe) whipped millions of its young men into a nationalist frenzy and sent them to bleed in the mud. Remarque’s book is about the horrors they experienced, but also the existential disillusionment the war instilled throughout an entire generation. Of the older patriarchs, teachers, and officers who sent he and his friends to the front, Remarque writes:

They were supposed to be the ones who would help us eighteen-year-olds to make the transition, who would guide us into adult life, into a world of work, of responsibilities, of civilized behaviour and progress - into the future. Quite often we ridiculed them and played tricks on them, but basically we believed in them. In our minds the idea of authority - which is what they represented - implied deeper insights and a more humane wisdom. But the first dead man that we saw shattered this conviction.

We were forced to recognize that our generation was more honourable than theirs; they only had the advantage of us in phrase-making and in cleverness. Our first experience of heavy artillery fire showed us our mistake, and the view of life that their teaching had given us fell to pieces under that bombardment.

While they went on writing and making speeches, we saw field hospitals and men dying: while they preached the service of the state as the greatest thing, we already knew that the fear of death is even greater. This didn’t make us into rebels or deserters, or turn us into cowards - and they were more than ready to use all of those words - because we loved our country just as much as they did, and so we went bravely into every attack. But now we were able to distinguish things clearly, all at once our eyes had been opened. And we saw that there was nothing left of their world.

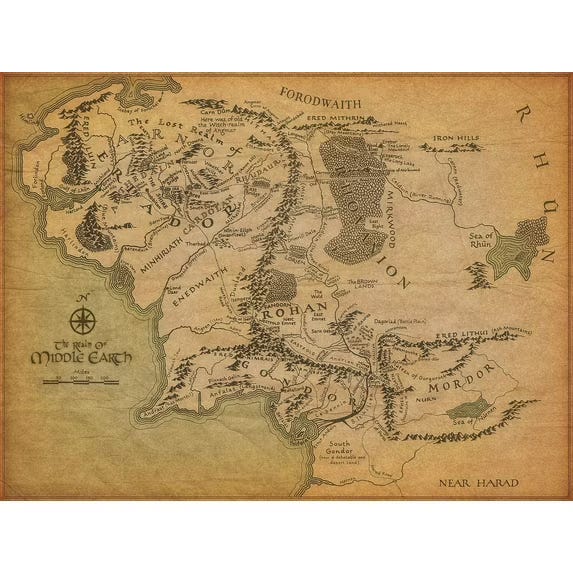

The Lord of the Rings, by J.R.R. Tolkien (1954-1955)

Look, I should be allowed at least one embarrassingly normie entry on a list like this and Tolkien’s trilogy is going to be it. Before this year, I had read it just once as a teenager and, by the time I was old enough to think about reading it again, the world of Middle Earth was increasingly overshadowed by the Peter Jackson film adaptations. Revising these books, I do think that’s a bit of a shame because, while the movies are undeniably well done and entertaining, they really do sacrifice much of the psychological depth and lore that makes the books so special. There is a kind of world building in the Lord of the Rings that few other series have ever matched. The scale of the storytelling is just unbelievable and, as a 12 or 13 year old, I don’t think I really could have appreciated how much is actually going on in these books or how completely their author thought through the complexities of his invented Middle Earth.

Structurally, the Fellowship of the Ring is just flawless: oscillating between places of safety (the Shire, Bree, Rivendell, Lorien) and chapters filled with danger (the Barrowdowns, Moria) until the very end. The Two Towers, for me anyway, ebbs somewhat in its second half — which mostly eschews politics and lore and is instead all about Gollum, Frodo, and Sam. I actually haven’t finished The Return of the King yet, but the section in Minas Tirath has been a highlight of the series upon revisiting.

I still have my dad’s childhood copies and, talking to him recently, he perceptively remarked that the Orcs are very much the weakest link in Tolkien’s lore. If they’re politically coded, they seen more or less a stand-in for the industrial working class — and, to a greater extent than anything to do with race, I think that’s where we find the locus of Tolkien’s small-c conservatism. In terms of world-building and storytelling, in any case, they’re uncharacteristically underdeveloped as a facet of Middle Earth. We never really see or get a feel for Orc society. Do the Orcs have a sense of their own history? Do they have inner lives of any kind? Why are they politically committed to Sauron? Hell, do they have sex? Are there female Orcs? Given how exhaustive Tolkien was in thinking through everything else about this world, there’s a glaring vacancy around one of its load-bearing features.

Hahah wasn’t expecting to find here LOTR ❤️

Also read the Richard Evans trilogy this year. Such an achievement to write a series so chock-full of information on such a breadth of subjects that still feels both compelling and easy to read (not counting the depressing nature of the subject material, of course). I was shocked how quickly I made my way through them.