Is this really what NDP renewal looks like?

The NDP's first official leadership debate did a disservice to the party, its members, to francophones, and to Quebec

Earlier this year, I renewed my membership in the New Democratic Party of Canada in anticipation of the party’s coming leadership race and its convention in Winnipeg early next year. I’ve voted in two so far (2012 and 2017), and this one feels particularly important. Having been reduced to just 7 seats and only 6.29% of the popular vote in last April’s federal election — the worst showing for both the NDP and its predecessor the CCF since the latter’s founding in 1932 — the next few years potentially represent a make or break moment for Canada’s parliamentary left.

Electorally, the party itself needs to recover. But beyond this it needs to debate and reckon with more existential questions of policy and purpose. That calls for a genuine process of renewal, not simply a rebrand, and NDP members deserve a leadership race characterized by vibrant, vigorous debate about the party and its future. This being the case, last Thursday’s debate in Montreal — the first of only two official debates currently scheduled — was a resounding failure, and watching it I felt a mixture of anger, frustration, and embarrassment.

In what follows, my purpose is not so much to criticize any of the candidates — who, among other things, were themselves done a disservice by the debate’s format — but rather to make some broader points about the debate and race itself.

Let’s start with the elephant in the room.

1) The “French debate” that wasn’t

“Le Francais n’est past la force des candidats” — TVA Nouvelles headline

In a November 17th release, party officials announced that the debate would “be held majority in French, underscoring the Party’s commitment to engaging Quebec and francophone communities.” But if this was the goal, it can safely be said the evening was actively counterproductive.

From the outset, this was quite explicitly billed as a French language debate — a fact further testified by the introductory remarks offered by Alexandre Boulerice (the NDP’s solitary Quebec MP) and the chosen moderator Karl Bélanger (its former Principal Secretary, a Quebec candidate in the 1990s, and part of its senior team during the Orange Wave of 2011).

That was, on its face, a somewhat confusing choice given the conspicuous lack of French within the leadership field. Among the five candidates, only Avi Lewis really seems conversant, with Edmonton-Strathcona MP Heather McPherson a fairly distant second. The three others — Rob Ashton, Tony McQuail, and Tanille Johnston — do not speak French at all. Ahead of the debate, it was announced some candidates would be permitted use of in-ear translators and that only 60% of the proceedings would actually take place in French.

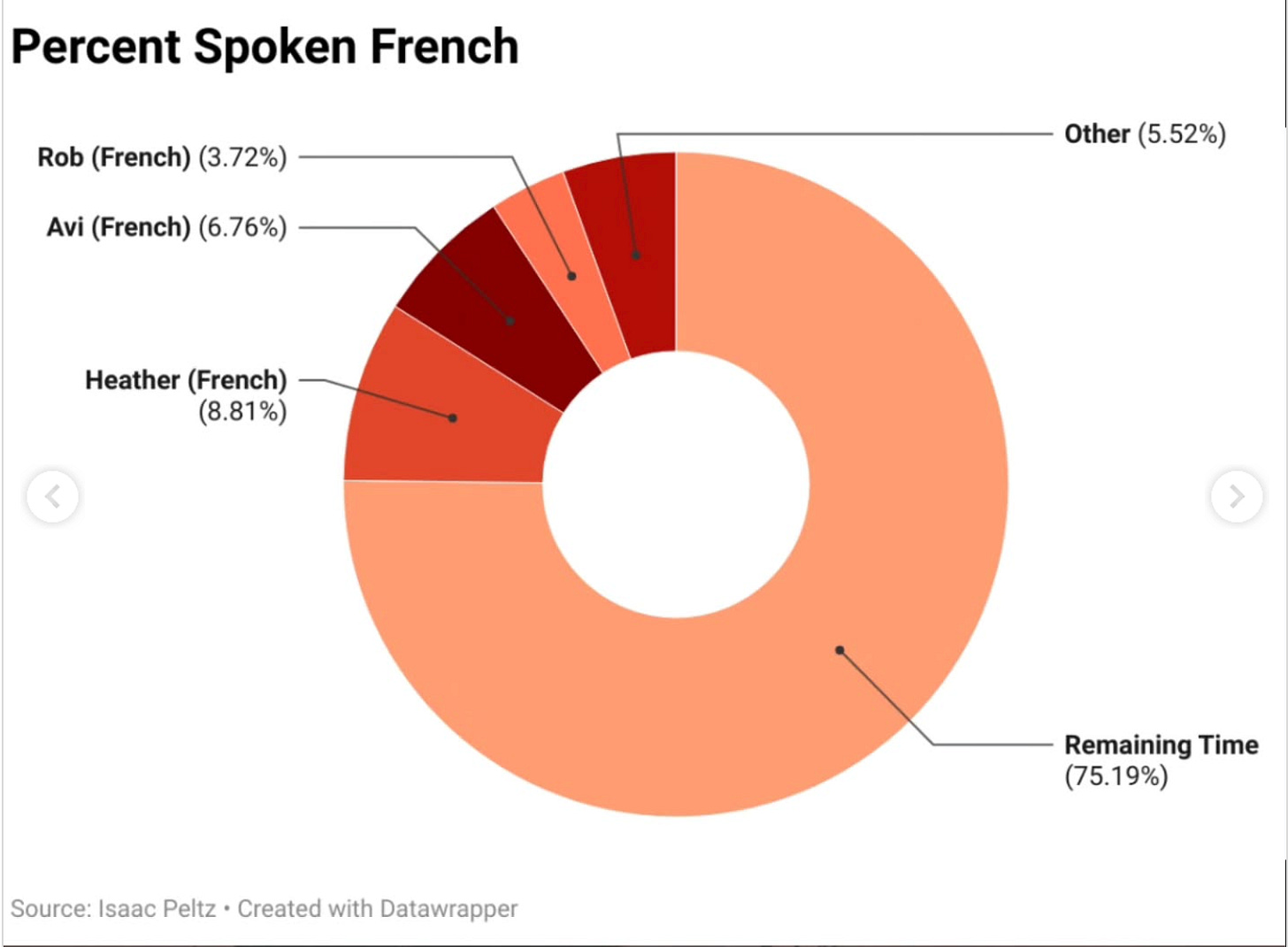

In the end, things fell well short of even this more conservative goal. According to this estimate from Isaac Peltz — who convincingly suggests that the party may well have violated its own stated rules for the race — only about 19% was actually carried out in French.

Even this, however, arguably understates things because much of the French spoken was so poor it might as well not have been. If you didn’t watch yourself, the clip found a few seconds into the Quebec media panel below will give you a good general flavour.

Things were only made worse in several of the post-debate scrums when — relieved of their notes and translation devices — three of the five candidates couldn’t understand questions put to them by French language journalists at all.

Since these limitations were well-known going in, it is nothing short of baffling that the party chose to brand the debate as it did, and the response has been predictably critical as a result. The two biggest winners, as Nora Loreto observes in her writeup, were probably the Bloc Québécois and the Liberals. The reaction in French language media, when it even took notice, has — to say the least — not been positive. Reacting to the headline “The NDP’s leadership candidates aren’t fluent in French. Will that hurt the party’s future?” the country’s best known francophone political journalist Chantal Hébert was characteristically blunt: “The short answer is yes…”.

Even Bélanger, the debate’s moderator, hasn’t minced words. “If you’re not able to speak French, to debate in French, you’re not gonna break through. Simple as that…If there is an election anytime soon, it will be difficult to be able to establish a connection with the Quebec voters.”

2) Does the NDP want to be a national party or not?

Further to this, and beyond the question of the debate’s erroneous branding, it’s worth underscoring what the failure of 3/5 candidates to address Quebecers in even passable French ultimately signifies for a national party. 22% of the Canadian population, nearly 1 in 4, speaks French as a first language. Within Quebec itself, — to state the obvious — it’s overwhelmingly the native language and, beyond this, absolutely foundational to both civic and cultural identity.

All of which is to say: it is more just a technical impediment for aspiring national leaders to be unable to understand or converse in the French language, and it’s simply untenable to minimize that or suggest otherwise. The phrase “English language rights” isn’t one you’d tend to hear in the rest of Canada. In Quebec, however, French language rights have had a significant political valence for more than a half century and have been an absolutely central question.

Before the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s, when Quebec was still a quasi-colony of English Canada (and a handful of US corporations) the linguistic divide often mapped directly onto the class divide. In one influential study of the industrial transformation of the 1940s, for example, Everett Hughes noted that the typical plant in Quebec consisted of unilingual francophones working in menial positions and unilingual anglophones in those of seniority, with a bilingual foreman typically serving as the “go between in the two worlds of labour and management”. Before the 1960s, urban francophones also tended to earn lower wages than their predominantly English-speaking bosses and often lived as tenants in properties owned by anglophone landlords.

That was certainly a long time ago, and a great deal has since been done to change things. But the fact remains that a party which aspires to be a genuinely national one cannot be if its leader cannot speak to Quebeckers in their own language and fails to fully recognize the significance of that language within Quebec itself.

Rob Ashton seems like a good guy and I understand what he was going for by saying “the language of the working class rises above any language in the world.” But, for the overwhelming majority of Quebec workers, the language of the working class is French, plain and simple, and there is simply no getting around that fact.

3) Surely, there is a better way to do this

Beyond issues of language and branding, the debate format itself left much to be desired.

At the beginning, technical difficulties plagued the livestream. Many of the questions — e.g. “What have you learned from successful NDP provincial governments?”, “Why do you want to be prime minister?” — were themselves unhelpfully vague and open-ended (this isn’t meant as a criticism of Bélanger, who I think did his best with questions I assume were handed to him). There was nothing about foreign policy, and plenty of other significant national and international issues went entirely unmentioned.

Speaking for myself, I badly want to see these people disagree about things and believe that the NDP’s current predicament calls for nothing less. We can take it as read that every candidate has basic progressive commitments, supports unions, is concerned about the cost of living crisis, and wants the NDP to win more seats in the next election than it did in the previous one. With that in mind, debates should be instead concerning themselves with issues that might — to the benefit of both NDP members and the public at large — elicit some constructive disagreement. On Thursday, questions of party organization and structure barely came up at all, but they deserve to be front and centre in the leadership race.

As a related point, my own view is that the party as a whole has too often lacked a healthy culture of constructive debate, both internally and in public. To some extent, this has to do with concerns about message discipline and so on. But — and I’m speaking partly here as a former staffer (federal and provincial) and ONDP candidate — I have often found there’s an institutional default to a kind of rigid positivity that can be very unhelpful. I’m not saying I want members and candidates to be at each other’s throats. But, if serious questions and issues cannot be meaningfully debated in a leadership contest after the party’s worst showing in roughly 93 years, when can they?

And, since we’re on the subject, there are too few debates scheduled in general. More informal events like the one recently held by a BC riding association and another held by the Douglas-Coldwell-Layton Foundation a month or so ago have been more substantive, and the party would be well-served to schedule more leadership events in various different formats.

The alternative is a sleepy and low visibility race in which badly-needed debates on important questions are lazily punted to some indeterminate point in the future.

If the party really hopes to renew itself, that simply won’t cut it.

As someone who has only ever voted for the NDP since coming to Canada, that debate was beyond frustrating...

Great observations 👍🏿