Between Seeger and Dylan

Reflections on the meaning of Newport '65

Late last year, I reviewed James Mangold’s film A Complete Unknown for the Toronto Star. Since the movie had just come out, I was more interested in writing about it as a movie than digging more deeply into the events it depicts (suffice it to say, I enjoyed A Complete Unknown despite some mostly friendly reservations and thought some of the performances were particularly good). In any case, Mangold drew on Elijah Wald’s 2015 book Dylan Goes Electric! Newport, Seeger, Dylan, and the Night That Split the Sixties, and if you’re unfamiliar with the background here that title should basically give it away.

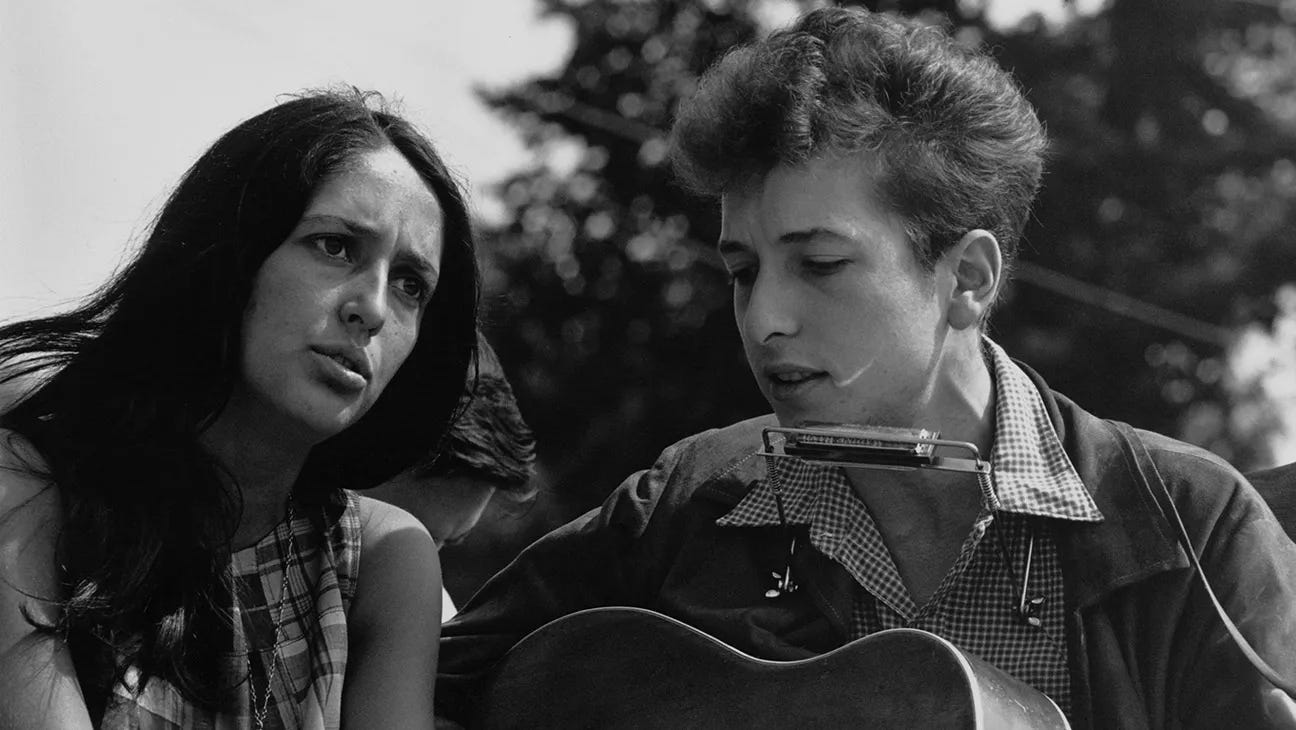

Wald’s book is a fascinating excavation of one of the most mythologized and talked about events in the history of popular music — namely, Bob Dylan’s famous (and highly controversial) electric set at the Newport Folk Festival on the evening of July 25, 1965. Dylan was just 24, and had become a mainstay at Newport in the preceding years. His songs — initially inspired by people like his hero Woody Guthrie and honed in the countercultural milieu of Greenwich Village — were cherished, not just for their poetry but for Dylan’s breathtaking ability to communicate deep social truths with no more than a guitar, harmonica, and a few simple chords at his disposal.

But on the evening of July 25, or so the legend goes, this old Dylan was suddenly gone. The new Dylan — the Dylan of Highway 61’ Revisited and Blonde on Blonde — sported dark sunglasses, wielded a Stratocaster, and sung with a backing band. Out were the folk stylings of The Times They Are a-Changin’, in was the abrasive crash of “Like a Rolling Stone.” As Wald writes in his book, the basic facts of what occurred are at this point so “obscured by a maelstrom of conflicting impressions” that the evening has long since taken on a mythic life of its own. To this day, it remains unclear how badly Dylan’s set was actually received by the audience. Some booed, some cheered, though no one can quite agree in what proportions.

Today, the myth of Newport really does matter more than the strict details of what actually happened. What’s generally seen to be at stake in the story has to do with competing conceptions of the artist — respectively personified in Mangold’s A Complete Unknown by Timothée Chalamet’s Dylan and Edward Norton’s Pete Seeger. In one particularly memorable scene just before the film’s climax, Seeger pleads with Dylan in a quivering voice:

SEEGER: Imagine a seesaw. A great big seesaw. One end is stuck to the ground because it has a basket full of rocks on it. And the other end is high in the air. There’s a basket on that end too, but its only half full - of sand - and the sand is leaking. Now, some of us, we have teaspoons - and one teaspoon at a time, we’re putting sand into that basket. It’s leaking out as we put it in - and people are laughing at us but every few days a new person shows up with a teaspoon, pitching in. We all keep going, Bobby. You know why?

DYLAN: Why?

SEEGER: Because one of these days, or years, or decades, who knows, enough people are gonna be using their little teaspoons all at once. And on that day, that basket of sand is gonna get so full that the whole damned thing goes “Zoop!” and level things out…Newport was purpose built to share traditional music, homespun music, people’s music, with other people, out in the air, in nature. And since we started, six years ago, more and more people have grabbed teaspoons. Spoons for peace. Spoons for justice. Spoons for love. Then you came along, Bobby…and you brought a shovel. We just had teaspoons. But you brought a shovel. And now, thanks to you, we’re almost there. You’re the closing act, Bobby, and if you could just use that shovel the right way-

DYLAN: [staring at the floor] The right way…

The scene is obviously a dramatic contrivance, but I think it nonetheless represents the tension between Seeger’s vision and Dylan quite effectively. For Seeger, folk music was a movement as well as a medium. It was not only a vehicle for individual creativity, but a collective project of social solidarity and a tool for political struggle. It was cooperative and conscious and, in many ways, its relative technical simplicity was the point. “To Seeger,” as Wald puts it, “folk music was defined by its relationship to communities and traditions: it was what nonprofessionals played in their homes or workplaces for their own amusement and the songs and music they handed down through that process to later generations. That did not mean it was better than the music of Beethoven or Gershwin, but it was different, and a big part of the difference was that it was shared, and no one owned or controlled it.”

Dylan’s formative years as a songwriter were mostly spent around those who shared the same communitarian ideal of the folk tradition. To this end, some of his best early songs lifted lines, chord progressions, and other stylistic hallmarks directly from others (an obvious example is Dylan’s “Song to Woody”, one of only two originals on his eponymous debut record, though also melodically identical to Guthrie’s song “1913 Massacre”). This was not, either for him or for others in the scene, an act of appropriation or plagiarism, but instead a quite natural expression of the folk ethos.

As Dylan grew older and more self-assured as an artist, he increasingly saw his own music quite differently — the very things earnest leaders of the folk scene like Seeger and Joan Baez valued most deeply feeling more and more like leaden weights around his neck. His very choice of songs at Newport ‘65, in fact, seemed intended to make this point.

When Dylan first stepped onstage in his leather jacket and howled the words “I ain’t gonna work on Maggie’s Farm no more…” those present may not have grasped their full meaning, but in retrospect it was all-too clear. Even his grudging concession to the audience’s expectations roughly fifteen minutes later — a solo, acoustic rendition of “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue” — ultimately carried the same message. When Dylan sang “You must leave now, take what you need, you think will last/But whatever you wish to keep, you better grab it fast…” he was offering a kind of defiant farewell to his audience. And maybe also to his former self.

In one way or another, the Dylan we’ve known since Newport ‘65 has been someone for whom songwriting is not a communal enterprise — let alone a technology of solidarity or protest — but instead a means for radical self-expression. For decades now, he has continued to experiment: relentlessly taking on new forms and identities while leaving his old self in the dust, only to then cast them too aside and be born anew. Much as the Dylan of July 25, 1965 was not the Dylan of the Gaslight Cafe, the Dylan of Blood on the Tracks is not the same one you hear on Highway 61’ or Bringing it all Back Home. Between 1961 and 1965, he composed some of the greatest folk songs ever written,1 quickly soaring high above his own idols and still more quickly leaving it all behind.

Whatever the decade, there’s a periodic yearning for transcendence in Dylan’s best music and also a deep appreciation for a wide breadth of different musical traditions. But beyond these somewhat abstract unities, he is fundamentally a shapeshifter: an artist who endlessly transfigures and refuses to keep his feet planted in the same spot for too long.

I have seen Dylan perform twice, and on each occasion he seemed both warmly familiar and completely impenetrable. Just like his audience, he has clearly formed complex relationships with his past selves and the vast back catalogue their decades of invention have cumulatively produced. By this point, I know hundreds of his songs intimately and have spent countless hours feeling them and thinking about what they mean (he clearly has too, which is presumably why he’s always rejigging and rearranging them).

Yet I don’t think any of us will ever really know Dylan himself. He’s so distant on stage in fact, and so prone to wearing giant hats that obscure his face that I’ve barely ever caught a direct glimpse of it in person. But his bottomless enigma will forever keep us coming back, and his songs will greet us like old friends even if their creator remains shrouded in the shadows.

I discovered Dylan’s music around the age of fourteen, and I expect I’ll be listening to it until the day I die. I have many favourite albums and have never really been a partisan for one era over another (though I’ve always been particularly partial to Bringing it all Back Home, which informally serves as the bridge between the pre-Newport Dylan and the electrified one). When it comes down to it, I think he’s basically a songwriter without peer — one of those rare people whose creative genius can rightly be called promethean.2 Across the entire history of human civilization and culture, from the days of Homeric poems to the present day, there is only a very small handful of artists, writers, and musicians for which the word meaningfully applies.

As it happens, I have a deep personal relationship with Pete Seeger’s music as well.

For the past decade or so, I’ve earned my living as a socialist writer, but I was not actually raised in a red diaper household, and so among other things came upon “Solidarity Forever” for the first time quite late. I’m not sure exactly when it was (probably in late teens) but I still vividly remember the experience of hearing to it for the first time. It was, as you’ve probably guessed, one of Seeger’s great renditions, and it struck a chord deep within my soul. I don’t mean to embellish and, at risk of sounding very earnest here, the song had a profound effect on me.

It was a complete moral revelation in just four verses and a chorus; a grand vision of transcendence, salvation, and universal emancipation all-in-one; true, pure, crystalline. Its message was earthly and secular, but nonetheless felt like a dispatch from some place beyond history, perhaps even beyond space and time. Injustice exists, it said, but collectively we can defeat it — not in the next world, but right here in this one with our own hands. It wasn’t just the words themselves, though they were certainly powerful. It was also the way Seeger and the chorus around him were singing them.