Werner Herzog, wanderer above the fog

Reflections on a great filmmaker — and his most criminally underrated work

Last weekend, my little effort here on Substack reached an important milestone: officially it is now a “bestseller” — which actually signifies nothing except that enough of you have signed up for paid subscriptions that the Luke Savage Substack qualifies for the little orange checkmark you’ll now see in my profile. In any case, I am as ever deeply grateful to the roughly 2,500 of you who have signed up to follow my work here. I love writing, even if the act itself is sometimes tedious, and I wouldn’t be able to do it on here if people weren’t willing to read, share, and discuss the things I publish.

In any case, if you haven’t taken out a paid subscription you can actually take out a free trial to get full access to the paywalled pieces and see if getting one would be worth it. From now until August 10th, I’m also offering annual paid subscriptions at a discount of 20% at this link so — as the humble auctioneer might put it — come on down!

Finally, you will have already seen that today’s piece has nothing to do with politics or the news. Something I’ve particularly enjoyed about this whole experiment so far is that it’s afforded me the opportunity to think about other things now and again. What follows is an original piece, though I did adapt a few sentences from an older essay that partly involves Werner Herzog’s criminally underrated film Heart of Glass (I cannot, alas, lay claim to the two stanzas below, for which credit is owed to the English poet Matthew Arnold). Enjoy.

-Luke

The Sea of Faith

Was once, too, at the full, and round earth’s shore

Lay like the folds of a bright girdle furled.

But now I only hear

Its melancholy, long, withdrawing roar,

Retreating, to the breath

Of the night-wind, down the vast edges drear

And naked shingles of the world.

Ah, love, let us be true

To one another! for the world, which seems

To lie before us like a land of dreams,

So various, so beautiful, so new,

Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light,

Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain;

And we are here as on a darkling plain

Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight,

Where ignorant armies clash by night.

-Matthew Arnold, Dover Beach (1867)

In the opening sequence of Werner Herzog’s 1976 film Heart of Glass, an unknown man sits with his back turned in a soupy fog, his only companions a herd of cattle grazing nearby. The man turns and the lens of Herzog’s camera shifts to show us his perspective, revealing a breathtaking vista of forests and mountaintops over which an ethereal blanket of clouds seems to be flowing with the smoothness of a running river. The still unknown and unnamed figure then offers a dark prophecy of disintegration and collapse:

I look into the distance to the end of the world. Before the day is over, the end will come. First, time will tumble, and then the earth. The clouds will begin to race... the earth boils over; this is the sign. This is the beginning of the end. The world's edge begins to crumble... everything starts to collapse... tumbles, fall, crumbles and collapses. I look into the cataract. I feel an undertow, it draws me, it sucks me down. I began to fall, a vertigo seizes upon me.

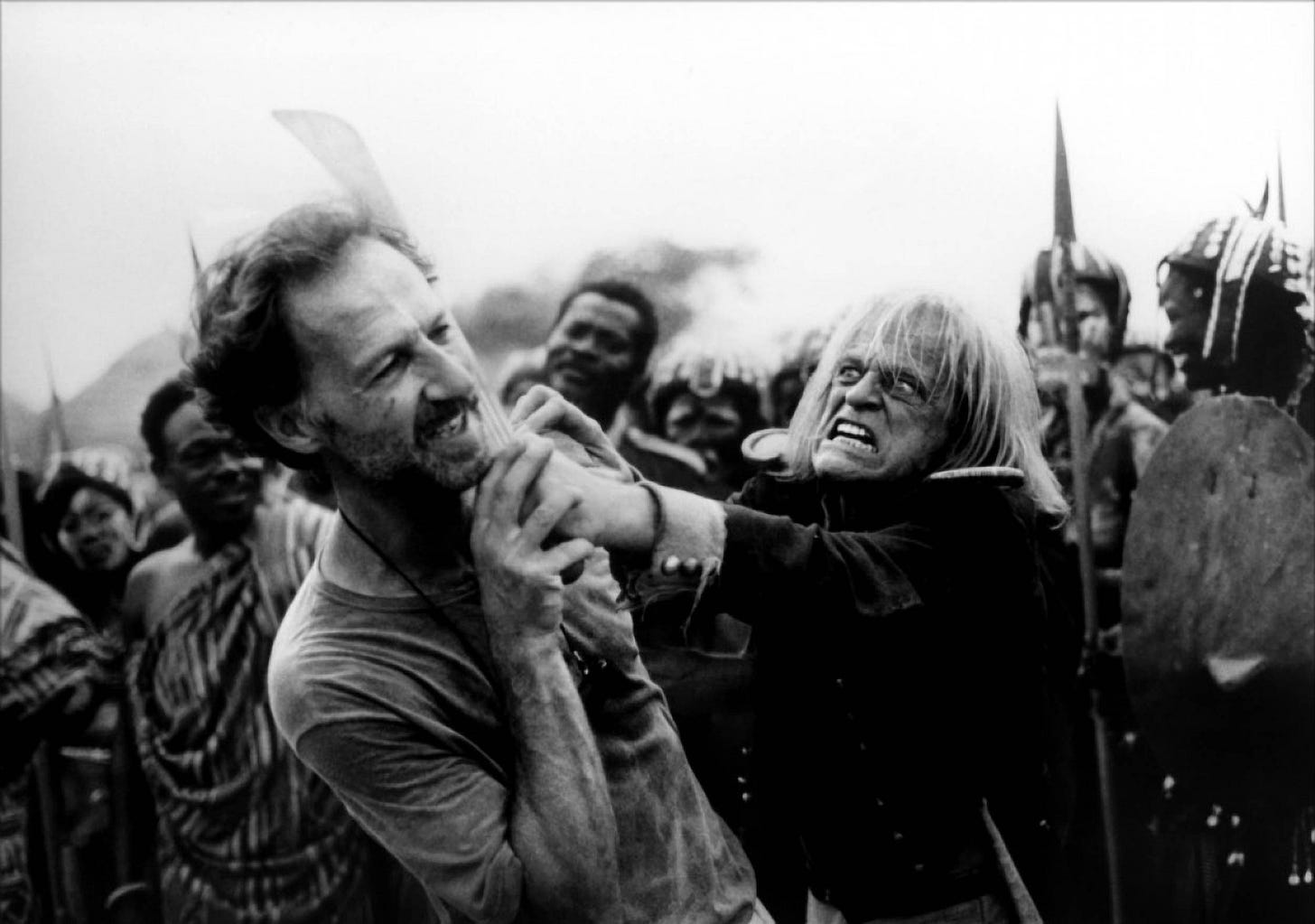

This opening — which borrows its imagery from the German Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich’s work Wanderer Above a Sea of Fog (1818) — is emblematically Herzogian, as is everything that follows it. Heart of Glass, the most consistently underrated and ignored of Herzog’s non-documentary films, tells the story of an 18th century village in rural Bavaria thrown into chaos and disorder by the death of its master glassmaker Mühlbeck. Directly or indirectly, everything in the village seems to have depended on Mühlbeck’s precious glass, and its value clearly transcends the parochialism of mere commerce.

Driven to madness, and maniacally obsessed with the glass (which he believes to have magical properties) the local baron orders a frenzied search for Mühlbeck’s formula. But this turns out to be a doomed mission. As the village’s craftsmen scramble in vain to reproduce the late master’s technique, its world gradually descends into chaos and madness. In this sense, Heart of Glass is a classical tragedy. By attempting to uncover an impenetrable secret, the townsfolk only fulfill the mountain seer’s prophecy and bring about their own destruction. The secret of the glass has died with Mühlbeck, and lies beyond the clutches of quantification or industry.

In what has always been my favourite scene from the film, the baron speaks cryptically to one of his servants:

Glass has such a fragile soul. It is immaculate. A crack, a sin; after sin there is no more sound. Will, in the future, we see the disappearance of factories — as we see in the ruined fortress — the sign of inevitable change?

[the servant, in reply] People say that Hias had a vision in which bushes invaded the glasswork. Lilacs aspire to the company of men. That’s what they say.

Then have Mühlbeck’s house demolished and let us look for its secret in every fissure. Let us dig the soil. Mühlbeck buried his secret…The untidiness of the stars, it makes my head hurt.

There are several ways one might interpret this very beautiful and challenging film (this is doubly true of its epilogue, which I haven’t even mentioned yet and might be worth a dedicated essay of its own). Heart of Glass obviously draws on Herzog’s own youth in rural Bavaria, which the director incidentally chronicled in his recent memoir as if it were itself a piece of old German folklore. The young Herzog’s world was a place inhabited by giants and witches; he grew up in a house that echoed “with mysterious creakings and hauntings” where he once “met God”, and held communion with rivers, streams, and fauna that almost seemed to speak.

As I wrote back in 2023, Herzog’s purpose in the book was not to offer us a literal chronicling of events — something seemingly lost on dimmer reviewers — but instead to convey the mythic power that memories, images, and history can retain beyond the strictures of pure fact. This, in itself, is a good summation of his entire creative project. Whether fiction or documentary, Herzog’s films have always in some way been about the ecstatic nature of truth and beauty: in the bubbling cauldrons of active volcanoes; in the thickets of the Amazon jungle; in the prosaic experiences of everyday life. They are stories driven by poetic imagination — by the eternal search, in his words, for something more “mysterious and elusive” than pure empirical fact.

This is, I think, what gives Heart of Glass its strange mythic power. Herzog’s film is foremost a tragic fable about the coming a disenchanted world, and all it has meant. The denizens of its doomed village — peasants, bürgers, and gentry alike — are all being pulled inexorably into the chaotic bustle of modernity; into a swelling tide of change that will soon wash away everything they have known. Small towns will grow into cosmopolitan metropoles. Craft will be replaced by industry, and factories will rise while old fortresses crumble. Social life will be standardized. Local administration will be supplanted by distant bureaucracy. Science and reason will become nature’s new masters, perhaps even masters of the human soul. This is a world where enchantment is already receding, and one that soon promises to vanquish mystery for good; a world that can no longer coexist with the deceased Mühlbeck or his ruby glass.

And yet, the glass — and its “fragile, immaculate soul” — will live on as a transcendent ideal even if it will never again exist in tangible form. Within the story itself, pursuit of that ideal ultimately drives the villagers into madness. In the director’s films, the same search has given us ecstatic images of truth and beauty that eclipse the myopic empiricism of the modern world. Like the unnamed wanderer in Friedrich’s painting, Herzog is here to remind us there is still something unknown and wonderful that lies beyond the clouds.

Heart of Glass my absolute Werner top pick - great piece Luke