"Wealthy New Yorkers who take the bus"

The liberal obsession with means-testing is both dogmatic and dishonest

Means-testing, the idea that public programs should necessarily be targeted or limited based on particular criteria, has been an obsession among liberal policy wonks since at least the 1990s. On one level, it’s a concept with intuitive appeal. Shouldn’t public programs and services, after all, be tailored to those who most need them? And, if someone can individually afford a private version of the same program or service already, why should the public be subsidizing them? Means-testing can often sound like a good idea because it so easily gels with both the rhetoric of efficiency and the language of social concern.

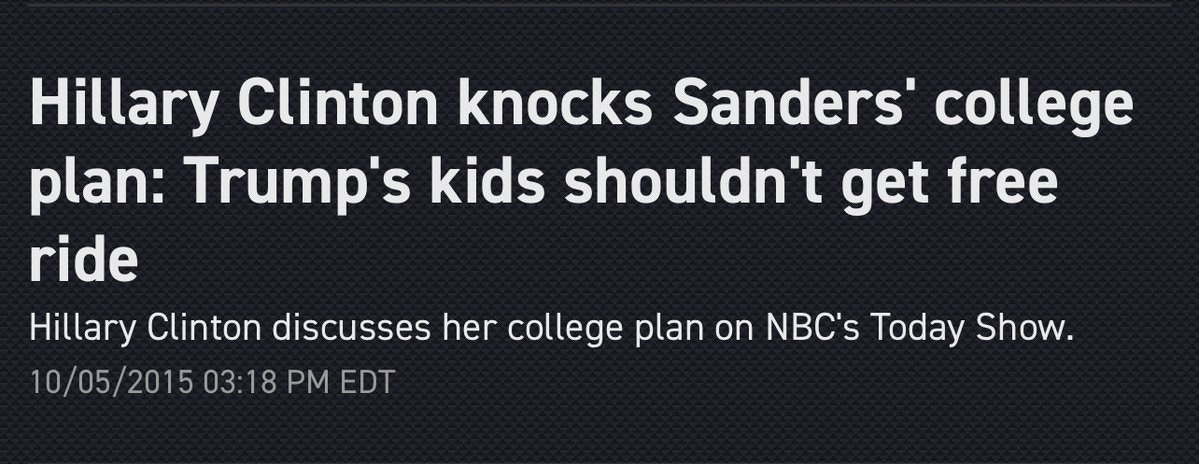

This is one reason, I think, it’s become a go-to for right leaning liberal politicians keen to look compassionate while reaffirming their managerial bona fides. If they happen to be personally wealthy, it can also double as a form of ersatz populism, a way of sounding class aware while functionally opposing the politics of redistribution. Oh, so, you want to give free stuff to rich people? Back in 2016, Hillary Clinton used exactly this line of attack against Bernie Sanders’ plan for free tuition at public colleges. A year earlier, Canada’s Justin Trudeau objected to universal childcare on the grounds that social benefits “shouldn’t go to rich families like [his].”

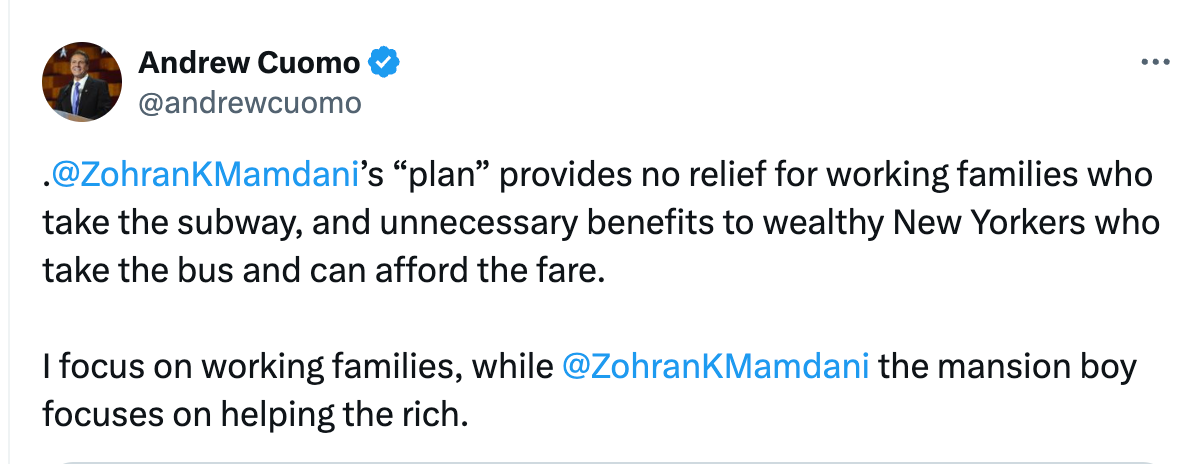

More recently, the same rhetoric has been taken up by the flailing Andrew Cuomo in his doomed bid for the New York mayor’s office — particularly in opposition to Zohran Mamdani’s plan for free bus service citywide. For his part, Cuomo proposes “making buses and subways free for low-income New Yorkers by expanding the existing Fair Fares program and providing free travel to residents on a means-tested basis.” As far as political rhetoric goes, Cuomo’s line of attack here is particularly silly. Like Clinton, he is an immensely wealthy politician relying heavily on the deep pockets of billionaire donors and, in office, was an enthusiastic champion of their interests. He is also suggesting there are legions of rich people making frequent use of public transit, a suggestion almost as ridiculous as Clinton’s implication that any of Donald Trump’s children would ever go to a public college.

Sliminess and hypocrisy aside, however, the substantive arguments typically marshalled by liberal politicians in favour of means-testing don’t hold up to scrutiny either. Granting some room for generalization, here are a few others to consider.

With a progressive tax system, universal programs and services do not, in fact, “subsidize the rich.”

All of us pay taxes to various branches of government — federal, local, and otherwise — but we also pay wildly different amounts based on our income level. Plenty of tax systems might be made a lot more progressive than they currently are, but the bottom line is that a well-off commodities trader pays a lot more in real terms to tax authorities than a teacher or janitor does. This inevitably means the former is disproportionately subsidizing public programs and services, not the latter.

Universal programs are almost always more efficient to deliver and administer. They’re often cheaper too.

Among the strongest cases for Mamdani’s free bus service plan is that it would probably make all of buses in New York City move a whole lot faster. As City Comptroller and Mandani ally Brad Lander recently pointed out: “The one thing that speeds buses up is making them free. Because if you don’t have that slow each person getting on the front of the bus and waiting, (and if) you don’t have the problem that bus operators have to be the ones to enforce the fare at the front of the bus, you dramatically reduce the amount of time buses spend boarding.” Eliminating the process of fare collection would also eliminate the need for bus drivers to do fare enforcement and, in turn (according to the president of the New York Transit Workers’ Union) dramatically reduce disputes between drivers and commuters.

By the same token, the likes of free transit and public healthcare also tend to reduce bureaucracy and eliminate vast amounts of paperwork. For all the purported efficiency of means-testing a program or service, doing so invariably requires complex systems of administration that often as cumbersome as they are costly. It’s no accident, for example, that Canada spends less as a share of its GDP on universal public health insurance than the United States does for a system in which tens of millions have no health insurance to speak of. In fact, it’s simple math.

Equality, not charity

All else aside, there is more a profound philosophical question at stake in debates surrounding universalism and means-testing. Is the public sector part of a co-operative/social enterprise or is it simply an appendage that exists to plug holes and dispense services to those who can’t afford them? In the latter view, the market determines the price of most things and the role of government is similar to charity. In practice, this often means that poor people receive an inferior quality of service. But it also changes the character of public services as a whole. When everyone uses or benefits from a program or service regardless of their income it is transformed from a commodity into a shared good: something with intrinsic rather than strictly monetary value.

Universal programs are easy to explain and understand. They’re also much harder to undermine.

Which of the following is easier to understand: free college tuition or “a student loan debt forgiveness program for Pell Grant recipients who start a business that operates for three years in disadvantaged communities”? This is obviously a rhetorical question, and it might similarly be asked which would be more effective if the goal is to allow more people to get an education without being burdened by crippling debt?

I won’t belabour the point here. Sometimes the best option, whether in the moral sense or in the interests of efficiency, really is just to have the government provide quality public services to everyone with no carveouts, means-testing, or other strings attached.

Rich people don’t even use private buses, let alone public ones.

If we can add some citizen oversight to these programs, it might go some way into addressing Liberal concerns about who deserves it and who doesn’t as well as Conservative concerns about organizational corruption.

I know we’re a long way from weaving citizens assemblies into our governance structures, but if we don’t start the conversation now we might never get there.