The world of yesterday

Wes Anderson and the limits of postmodern nostalgia

I regret that Wes Anderson’s latest film The Phoenician Scheme did not really work for me. There is plenty going on in this movie that will be familiar to anyone who knows, and enjoys, his style.

The Phoenician Scheme looks just as elegant as your typical Anderson flick. It features an ensemble cast and a host of sardonic characters who speak in a stylized deadpan that is usually somewhere between sincerity and irony. It is supposedly set in 1950, but its reference points are unsurprisingly drawn from a much wider melange of culture and history. Its main character Anatole "Zsa-Zsa" Korda (Benicio del Toro) lives in a 16th century Italian mansion, and its main plot feels mostly like a device for showcasing its pastiche aesthetic. Its fictionalized kingdom, “Pheonicia” — presumably named for the ancient Mediterranean trade culture — is vaguely Near Eastern in appearance but also, for some reason, has revolutionaries who resemble Black Panthers and Americans who sport hoodies you might pick up at the gift shop of an Ivy League university.

Plenty of different themes are nodded at as well — modernization, industrialism, mortality, faith, Cold War espionage, familial estrangement. But they really are mostly nodded at rather than explored. Much like the visual and historical hodgepodge that makes up the film’s aesthetic, the story itself feels more like an impressionistic riff on other stories (or perhaps kinds of stories). In one scene, Del Toro’s character — a wealthy industrialist apparently based on an Armenian oil magnate named Calouste Gulbenkian — reads a book called Important Patrons of the High Renaissance. As best as I can tell, this too is fictionalized and, appropriately, The Phoenician Scheme often feels like something whose plots and images have been plucked from some kind of encyclopedia or chronicle of notable aesthetics from the past. There is artful stylization here, but to what end? There is a narrative and visual intricacy that is formally quite impressive. But, again, what higher purpose does it really serve?

I don’t want to sound too down on Anderson, who has made plenty of movies I both enjoy and genuinely admire. He is an artist with a distinct point of view that is his own, whose films have become instantly recognizable and — whether they ultimately succeed or fail — I really believe this counts for something in a cultural landscape that is increasingly derivative and homogenized.

Anderson’s elegant, involute formalism has also sometimes given us great beauty, and his greatest film, in my opinion, is also one of his most intricate. By containing its stories inside one another, The Grand Budapest Hotel — inspired by the work of the Austrian writer Stefan Zweig, and particularly his 1942 chronicle of late Austria-Hungary The World of Yesterday — only succeeds in offering us a nostalgic reverie for a lost European modernity, but also manages to say something quietly profound about the porous nature of memory. His more recent short film The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar employs a similar structure to great effect, and is a charming (albeit more minimalistic) showcase of Anderson’s style that is well worth a watch.

In any case, The Phoenician Scheme exhibits many of the same problems I detailed in a 2021 essay for Jacobin about his film The French Dispatch. For what it’s worth, I liked it more than I liked either The Phoenician Scheme or Asteroid City (perhaps the only one of Anderson’s more recent movies I couldn’t really connect with at all). But I ultimately found the same tension in the filmmaker’s style, and the same limitation in how he sometimes chooses to render our pasts.

Enjoy.

In a recent write-up on the new Marvel flick Eternals, NPR reviewer Glen Weldon looks to discover a silver lining in the release of yet another superhero monstrosity. Acknowledging that the whole genre has by this point become a kind of cultural white noise, he nevertheless proceeds to find a sonorous whisper amid the din — in this case, the artistic imprint of indie director Chloe Zhao, whose influence is “all over Eternals.” Well, not quite. Because, as Weldon himself acknowledges, the Marvel Cinematic Universe’s (MCU) leaden, formulaic aesthetic still dominates the movie so much that flickers of the director’s own style are, at best, a negligible presence: “You’d be forgiven,” he writes, “for assuming that Zhao’s directorial presence would get buried, caught up in the gears of the MCU machine and ground into the same uniformly fine powder that gets baked into every Marvel movie. And it does get ground up, to a certain extent. But not entirely.”

The result, Weldon argues, is a film which “pushes back” against the standard complaints issued by those who “harbor a performative disdain for Marvel’s cinematic output” and, presumably, against those of us who find fault with the exhausting uniformity of the entire superhero genre. With no shade intended toward Mr Weldon, it’s a sorry statement about the current cultural landscape that the faint presence of an individual director’s style is now such a rare event that it’s one we’re invited to celebrate. The movies, it would seem, have grown so utterly homogenous that even the slightest deviation from the usual assembly-line format is supposed to be transgressive and avant-garde.

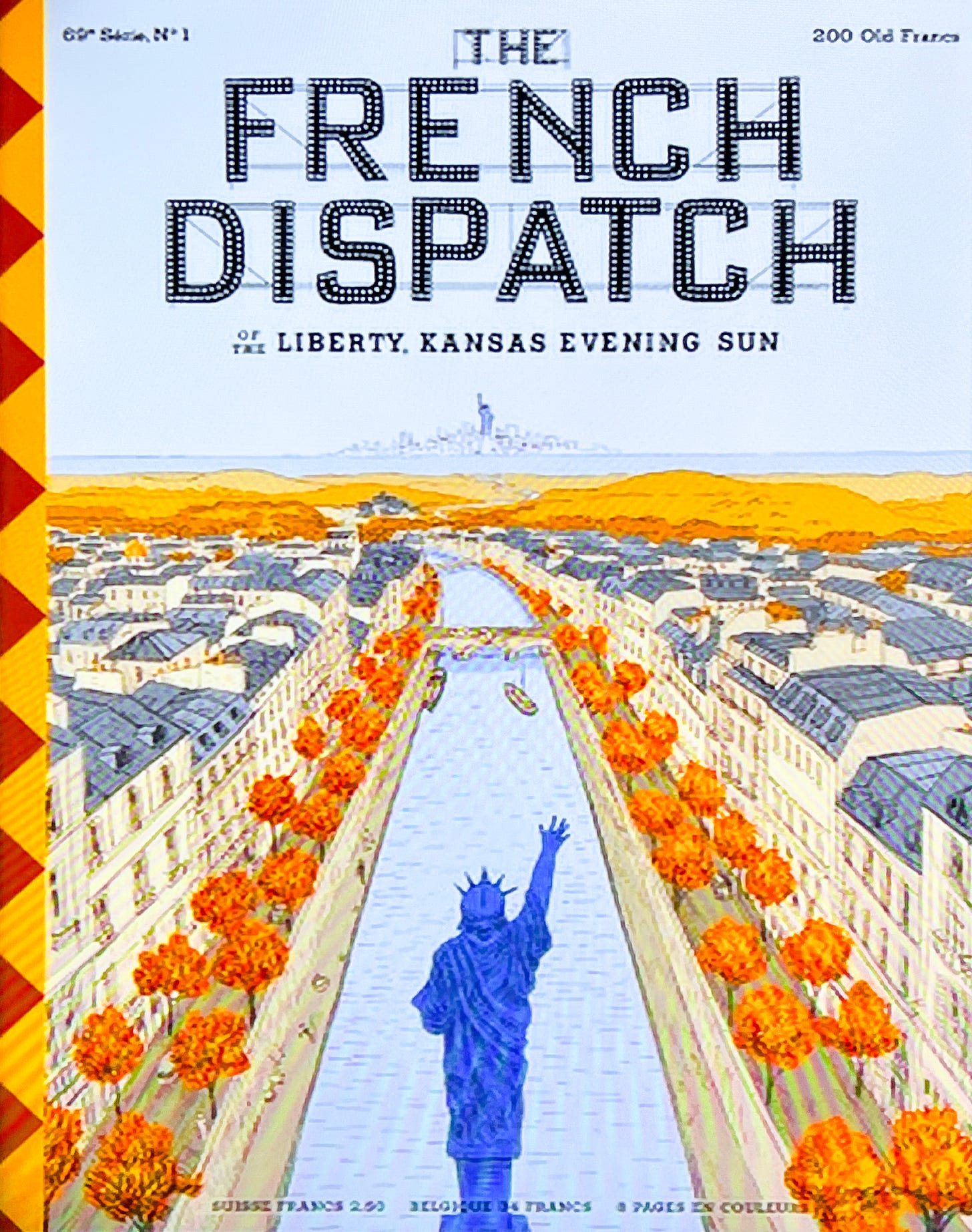

It’s in this context that we should situate The French Dispatch (full title: The French Dispatch of the Liberty, Kansas Evening Sun), the new anthology film from Wes Anderson — a director whose style is so distinctive that you invariably recognize it right away. This may be anecdotal, but I suspect my own arc with classic Anderson films like The Royal Tenenbaums, Moonrise Kingdom, and The Grand Budapest Hotel is one probably shared by others from my generation. I discovered his movies in my late teens and was earnestly transfixed by their ornate beauty and whimsy. With a few years of cinema studies and a lot more films under my belt, I then mostly consigned them to the realm of undergraduate fancy, holding them to be amusing trifles more than beloved objects.

I’ve found it difficult to sustain this somewhat curmudgeonly view in my thirties, perhaps because mass culture is now so homogeneously schlocky that anything possessed of an individual artist’s point of view does, indeed, feel worth celebrating. The French Dispatch couldn’t have been made by anyone but Wes Anderson. And, like all his films, it is positively brimming with pleasant moments, sardonic irony, and earnest charm. If you aren’t among those put off by the filmmaker’s distinctive schtick, it’s a meticulously stylized banquet of visual delights that you’ll thoroughly enjoy (even if the anthology format leaves it slighter in scope than the epic Grand Budapest Hotel).

By way of summary, The French Dispatch is nominally about an American expat newspaper based in the fictionalized French city of Ennui-sur-Blasé (roughly “Boredom-on-the-World-Weary”). The eponymous periodical, however, is more of a loose foil than an actual subject — the majority of the film consisting of three long vignettes (with one shorter one), each dealing with a different story published during the paper’s multi-decade history (we learn in its opening frames that the editor, Arthur Howitzer Jr, has passed away and that the staff is planning to publish a retrospective farewell issue at his posthumous request).

In the brief “The Cycling Reporter,” travel writer Herbsaint Sazerac (Owen Wilson) gives a tour of Ennui-sur-Blasé and compares its past and present; in “The Concrete Masterpiece,” disturbed and imprisoned artist Moses Rosenthaler (Benicio Del Toro) paints abstract nudes of guard Simone (Léa Seydoux) and, through the effort of an unscrupulous art dealer, becomes an implausible sensation; in “Revisions to a Manifesto,” Lucinda Krementz (Francis McDormand) profiles a group of student radicals headed by Zeffirelli (Timothée Chalamet) as they stage a “chessboard revolution,” and briefly becomes sexually involved with him; in “The Private Dining Room of the Police Commissioner,” writer Roebuck Wright (Jeffrey Wright) recounts a frantic and somewhat tangled narrative involving food, police, and a ransom kidnapping.

At film’s end, a postscript from the director himself announces The French Dispatch as a tribute to many of his favorite New Yorker writers, offering a list of names that includes Joseph Mitchell, Lillian Ross, and James Baldwin — whose likenesses and personalities loosely inspire various characters throughout. “We were stealing things very openly,” Anderson cheerfully told the New Yorker in a September interview, “so you really can kind of pinpoint something and find out exactly where it came from.”

The film’s endless use of pastiche is both what lends it its charm and where it ultimately hits a wall. As a stylist, Anderson is incredibly gifted, possessing an effortless command of modernist film techniques and variously evoking French masters like Jean-Luc Godard, Jacques Tati, and François Truffaut. His nostalgic appreciation for the sights, sounds, and aesthetic stylings of earlier eras also extends to people, places, and objects, many of which are composites drawn from multiple sources. Ennui-sur-Blasé feels at once both a town and a city — not quite Paris but also, as the New York Times’ A. O. Scott puts it, not quite not Paris either. Editor Arthur Howitzer Jr is (according to Anderson himself) a hybrid of actual New Yorker editors Harold Ross and William Shawn. Even the film’s structuring device carries a similar ambiguity. The French Dispatch newspaper visually resembles the New Yorker, but is clearly also inspired by expatriate publications like the now defunct International Herald Tribune.

This composite style gives Anderson’s universe a decidedly ethereal historicity — with images, people, and events seeming to exist in multiple periods at once. In The French Dispatch, as in The Grand Budapest Hotel, history itself comes in the form of pastiche; as ambient echo rather than straightforward retelling. This is most apparent during the “chessboard revolution” sequence, where May ’68 is not quite May ’68 but also not quite not May ’68: whimsical student militants rebel against “a thousand years of Republican authority” while seeking to destroy a “neoliberal imperialist project,” and Timothée Chalamet plays a kind of manic-pixie-dream version of Daniel Cohn-Bendit.

It’s all a romping good time, but both people and events are so de-historicized that the payoff is largely an amused sense of nostalgia that lacks a creative thesis beyond how things look and feel. Anderson’s project is a highly appreciative one and, for what it’s worth, he clearly intends to pay tribute to his subjects rather than patronize them. The resulting ironic distance, however, can turn his subjects into gossamer, evoking them as detached reference points rather than solid or tangible objects. This is in marked contrast to some of Anderson’s biggest influences — particularly figures from the French New Wave like Godard — who believed deeply in the political (and even revolutionary) potential of cinema and actively sought to conscript it in the service of political ends.

This is not a knock on Anderson or his style per se. The French Dispatch is a very entertaining and beautiful film, and I’d happily sit through it a dozen more times before going to see most of the movies that now tend to make it into theatres. In an age of assembly-line culture and CGI-induced visual uniformity, Anderson’s kaleidoscopic nostalgia for the sights, sounds, and tastes of earlier eras is both refreshing and praiseworthy.

Nostalgia, however, isn’t the same thing as memory, and to really remember earlier eras we must ultimately retrieve much more from them than sensuality, ambiance, and vibes. This, in turn, can have the effect of inspiring an altogether different kind of nostalgia: for a time before our collective sense of history’s forward momentum had ground to a halt; for a past that appeared to us as something real and tangible rather than as a quasi-ironic object to be rendered in glistening effigy after history’s end.