The Culture War is Completely Exhausted

A half decade into the 2020s, the 2010s may have finally come to an end.

Throughout the culture war flareups of the last 15 years or so, liberals and conservatives have periodically traded fire over matters that are fundamentally symbolic, and often negligible to meaningless at the level of actual political substance. In their own different (and often quite cynical) ways, both factions have been adept at converting cultural issues into the language of political grievance and, in turn, into supposed forms of political engagement — and even activism — that have often amounted to little more than new kinds of shopping or media consumption.

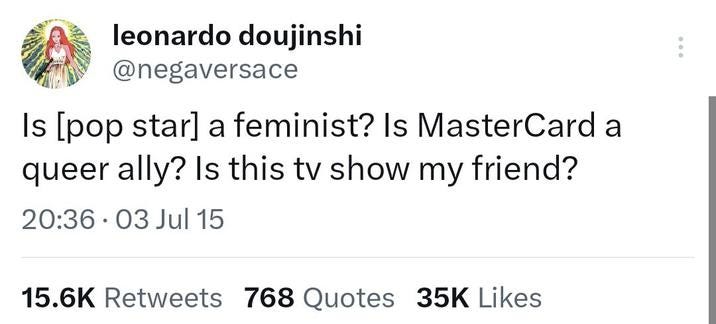

In retrospect, much of this stuff seems even more ridiculous now than it did at the time. And, without rehashing the by now well-worn left wing critique of it — that cultural consumption isn’t politics; that political elites deliberately retreat to cultural terrain to skirt more substantive political and material issues etc. — that very much still applies. Nonetheless, in the heady days of the 2010s, when among other things social media was still relatively new, plenty across the ideological spectrum did, by all appearances, earnestly ascribe real political weight to these sorts of controversies.

There has always, of course, been a fair share of cynical opportunism at work too. Political elites who functionally agree on the basic contours of the system as a whole need endless fodder for their partisan spectacle. Cable networks and engagement-farming websites similarly need their eyeballs and their clicks, and where better to find them than in endless cycles of quasi-manufactured outrage over the shows and ads people happen to be seeing on TV or the cereals they are choosing to eat for breakfast?

At the core, however, liberal and reactionary culture warriors have shared one fundamental premise in common: namely, the belief that politics is ultimately downstream from culture and, consequently, that the likes of the media people consume and the places they shop represent important and consequential sites of political struggle. For the right’s part, there has sometimes been a weirdly psychosexual dimension to this belief (case in point: Tucker Carlson’s anguish over the supposed desexualization of green M&Ms). For liberals, it has often tended more towards the shallow transposing of quite legitimate political demands (e.g. for racial justice or for greater social inclusion) into market logics.

Some might disagree with me here, but in both cases my sense is that this kind of cultural politics — notwithstanding its partially top-down nature — once had plenty of honest buy-in from below. And I don’t think it’s hard to see why. Whatever our political persuasion happens to be, the fact is that most of us feel pretty powerless when it comes to affecting any sort of profound political change in the societies that surround us. Politics, which is to say politics of the actual kind, feels increasingly sclerotic while political power itself feels ever-more distant and abstract. There’s thus a quite natural instinct, I think, to retreat to terrain where we have a surer footing and can experience a greater sense of agency and control. In this respect, our consumption habits and cultural tastes are obviously prime candidates.

Without being too definitive here, however, it’s my strong sense that this phase of the culture war is increasingly running on fumes — if only because the same things have been incessantly invoked and weaponized to the point of near total dullness. Again, I think political persuasion is largely irrelevant. When the same big red button has been smashed again and again and again there are bound to be diminishing returns regardless of the ideology or audience.