The air of equality

Orwell's Aragón and the atmosphere of socialism

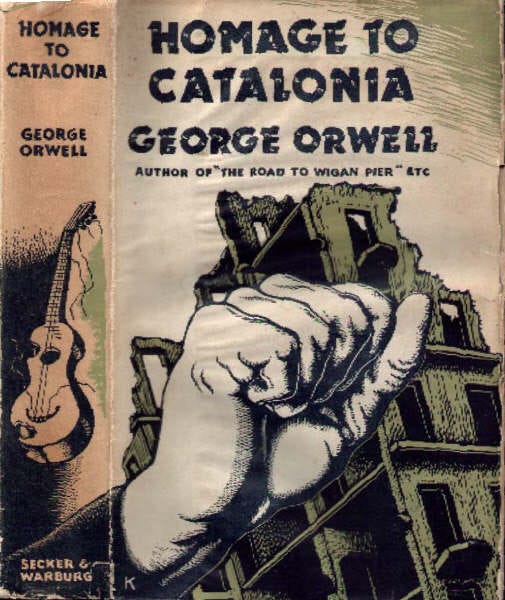

In 1936, George Orwell left England for Spain with the intention of covering its civil war for the New Leader newspaper. Arriving in Barcelona at the end of the year, he writes in Homage to Catalonia, he discovered an atmosphere unlike anything he had ever experienced before:

The Anarchists were still in virtual control of Catalonia and the revolution was still in full swing. To anyone who had been there since the beginning it probably seemed even in December or January that the revolutionary period was ending; but when one came straight from England the aspect of Barcelona was something startling and overwhelming. It was the first time that I had ever been in a town where the working class was in the saddle.

Practically every building of any size had been seized by the workers and was draped with red flags or with the red and black flag of the Anarchists; every wall was scrawled with the hammer and sickle and with the initials of the revolutionary parties; almost every church had been gutted and its images burnt. Churches here and there were being systematically demolished by gangs of workmen. Every shop and café had an inscription saying that it had been collectivized; even the bootblacks had been collectivized and their boxes painted red and black. Waiters and shop-walkers looked you in the face and treated you as an equal. Servile and even ceremonial forms of speech had temporarily disappeared. Nobody said 'Señor' or 'Don' or even 'Usted'; everyone called everyone else 'Comrade' and 'Thou', and said 'Salud!' instead of 'Buenos días'.

Orwell, needless to say, promptly decided he would rather shoot at fascists than try to cover the war as a passive correspondent. Joining the POUM — an anti-Stalinist faction of the republican army whose reigning tendency was libertarian socialism — he disappointingly found himself deployed to a theatre of the war where very little was happening. Life at the front, as he describes it, was an experience mainly defined by boredom and discomfort. And, when his unit was rotated away from the front after a few months, Orwell felt dispirited:

When we went on leave I had been a hundred and fifteen days in the line, and at the time this period seemed to me to have been one of the most futile of my whole life. I had joined the militia in order to fight against Fascism, and as yet I had scarcely fought at all, had merely existed as a sort of passive object, doing nothing in return for my rations except to suffer from cold and lack of sleep.

Later, however, Orwell realized that the relative torpor of his time with the POUM militia on the Aragón front had obscured something much more profound. In what has always been my favourite passage from the book, he quite vividly recounts the “atmosphere of socialism” he had discovered, if only for a short time:

The essential point is that all this time I had been isolated—for at the front one was almost completely isolated from the outside world: even of what was happening in Barcelona one had only a dim conception—among people who could roughly but not too inaccurately be described as revolutionaries. This was the result of the militia-system, which on the Aragón front was not radically altered till about June 1937. The workers' militias, based on the trade unions and each composed of people of approximately the same political opinions, had the effect of canalizing into one place all the most revolutionary sentiment in the country. I had dropped more or less by chance into the only community of any size in Western Europe where political consciousness and disbelief in capitalism were more normal than their opposites. Up here in Aragón one was among tens of thousands of people, mainly though not entirely of working-class origin, all living at the same level and mingling on terms of equality.

In theory it was perfect equality, and even in practice it was not far from it. There is a sense in which it would be true to say that one was experiencing a foretaste of Socialism, by which I mean that the prevailing mental atmosphere was that of Socialism. Many of the normal motives of civilized life—snobbishness, money-grubbing, fear of the boss, etc.—had simply ceased to exist. The ordinary class-division of society had disappeared to an extent that is almost unthinkable in the money-tainted air of England; there was no one there except the peasants and ourselves, and no one owned anyone else as his master. Of course such a state of affairs could not last. It was simply a temporary and local phase in an enormous game that is being played over the whole surface of the earth. But it lasted long enough to have its effect upon anyone who experienced it. However much one cursed at the time, one realized afterwards that one had been in contact with something strange and valuable.

One had been in a community where hope was more normal than apathy or cynicism, where the word 'comrade' stood for comradeship and not, as in most countries, for humbug. One had breathed the air of equality. I am well aware that it is now the fashion to deny that Socialism has anything to do with equality. In every country in the world a huge tribe of party-hacks and sleek little professors are busy 'proving' that Socialism means no more than a planned state-capitalism with the grab-motive left intact. But fortunately there also exists a vision of Socialism quite different from this. The thing that attracts ordinary men to Socialism and makes them willing to risk their skins for it, the 'mystique' of Socialism, is the idea of equality; to the vast majority of people Socialism means a classless society, or it means nothing at all. And it was here that those few months in the militia were valuable to me. For the Spanish militias, while they lasted, were a sort of microcosm of a classless society. In that community where no one was on the make, where there was a shortage of everything but no privilege and no boot-licking, one got, perhaps, a crude forecast of what the opening stages of Socialism might be like. And, after all, instead of disillusioning me it deeply attracted me. The effect was to make my desire to see Socialism established much more actual than it had been before…

…This period which then seemed so futile and eventless is now of great importance to me. It is so different from the rest of my life that already it has taken on the magic quality which, as a rule, belongs only to memories that are years old.

This passage is particularly special because it conveys a deeper truth that is often lost in discussions about capitalism and socialism. For much of the 20th century — and in the 19th as well — socialist critique variously focused its fire on the immoral character of the class society; on the chaotic irrationality of markets; on the need to win fair wages and liberate people from toil. The classless society, its utopian ideal, came in different forms as well. Sometimes it was a world of leisure, though elsewhere it was one of collective achievement; of creative and productive forces effectively marshalled and organized around a higher social purpose; of a material existence planned and coordinated by the working class itself. The telos of socialism also varied, but the narrative of historical materialism — through which the world was moving inexorably towards collective emancipation thanks to the inherent contradictions of capitalism — was by far the most powerful.

In any case, the effect here could be one of either economistic or idealistic abstraction.

There was, however, often a more immediate and humanistic current at work as well. One thing that has always struck me in the speeches and writings of early and mid-20th century socialists — be they politicians, trade unionists, artists, or anti-fascist partisans — is the extent to which their vision is quite specifically one of moral improvement. A socialist society, in this view, would not only be a place of greater justice and greater material equality. It would also be one in which both people, and the nature of the relationships between them, was profoundly transformed.

More than anything else, I think this is what Orwell’s passage captures so beautifully. As a way of being, modern inequality creates hierarchies of wealth and power, but in doing so it also fosters a culture, or perhaps an atmosphere, of inequality. In Spain, Orwell — if only for a short time — inhaled an altogether different atmosphere, and the effect on him was so powerful he never forgot it.

A great passage from a truly great book. Thanks for highlighting it. The phrase "where the working class was in the saddle" has been burned into my consciousness since the first time I read this book. A society "where political consciousness and disbelief in capitalism were more normal than their opposites" still appeals to me.

Orwell was tasting what humanity tasted quite a bit in the last 300,000 years. See Alvin Finkel's Humans: The 300,000 year Struggle For Equality.