Fascinating Fascism

On the artistic and moral cowardice of Leni Riefenstahl

The increasing proletarianization of modern man and the increasing formation of masses are two sides of the same process. Fascism attempts to organize the newly proletarianized masses while leaving intact the property relations which they strive to abolish. It sees its salvation in granting expression to the masses-but on no account granting them rights. The masses have a right to changed property relations; fascism seeks to give them expression in keeping these relations unchanged. The logical outcome of fascism is an aestheticizing of political life…All efforts to aestheticize politics culminate in one point. That one point is war.

— Walter Benjamin, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction

Last weekend I watched Andres Veiel’s new documentary about Leni Riefenstahl, which draws heavily on personal archival material recently turned over by her estate.

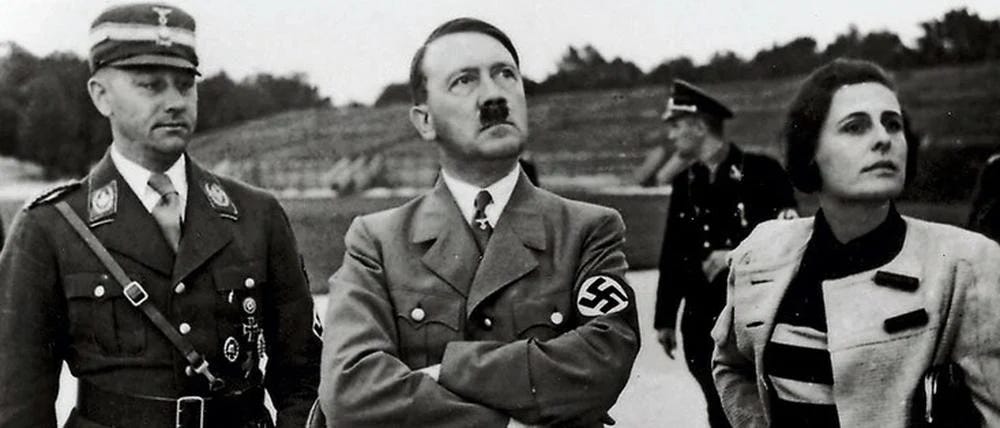

Riefenstahl (1902-2003), for those who don’t know, was both one of the most technically gifted documentary filmmakers of the 20th century and one of the chief cinematic propagandists for the Third Reich. Plenty of propaganda works from Nazi Germany and elsewhere were dull and formulaic by design; artlessly produced for the sake of broadness and visibly lacking in technical flair. Riefenstahl’s films, in contrast, were often terrifyingly innovative in both style and technique, and Riefenstahl herself became a much beloved figure within Hitler’s inner circle as a result. Her most famous films Triumph of the Will (1935) and Olympia (1938) show us the moral and aesthetic vision of the Nazi regime as its ideologues viewed it themselves: expressing in visual terms the reactionary modernism that had lurked behind their appeals to tradition from the very beginning. If fascism, as Walter Benjamin famously observed, tends towards the aestheticization of politics, Riefenstahl was one of its major artistic vanguards.

She was also, in her postwar life, a shameless fabulist who relentlessly asserted her own naive innocence about the true nature of the Nazi project: insisting with a straight face that she had simply been a fly on the wall, and that films directly commissioned by Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbles were somehow politically neutral. As one US intelligence officer sent to arrest Riefenstahl put it in 1945 : “She gave me the usual song and dance. She said, 'Of course, you know, I'm really so misunderstood. I'm not political.’” During de-Nazification, Riefenstahl was detained by Allied forces and tried several times for her association with the regime. Though officially deemed a fellow traveller, she eventually resurfaced as a public figure: publishing books, doing interviews, and finally making 2002’s Impressions Under Water (a documentary about sea creatures).

In some ways, Veiel’s documentary doesn’t tell us anything we didn’t already know. Riefenstahl’s claims of youthful innocence were always deeply unconvincing to anyone who had actually seen her films, and no serious person can come away from Triumph of the Will with the impression her gaze was dispassionate or ideologically unsympathetic. In the mid-1970s, no less than Susan Sontag penned a searing evisceration for the New York Review of Books (whose title I have here borrowed in tribute) occasioned by Riefenstahl’s two photography collections The Last of the Nuba and The Nuba People of Kau. The text on the latter’s dust jacket, incidentally, is a good demonstration of the little sleights of hand Riefenstahl and her publicists employed to sanitize her image.

An excerpt:

It was during Germany’s blighted and momentous 1930s that Leni Riefenstahl sprang to international fame as a film director. She was born in 1902, and her first devotion was to creative dancing. This led to her participation in silent films, and soon she was herself making—and starring in—her own talkies, such as The Mountain (1929). These tensely romantic productions were widely admired, not least by Adolf Hitler who, having attained power in 1933, commissioned Riefenstahl to make a documentary on the Nuremberg Rally in 1934.

This passage, as Sontag pointed out, is a mixture of propagandistic euphemism and invented facts. There is no such film as 1929’s The Mountain (though Riefenstahl did appear in Arnold Fanck’s 1926 film The Holy Mountain). Riefenstahl also starred in films from the get-go, making the hardscrabble narrative implicitly asserted in the above equally dishonest.

More to the point, as Sontag writes:

It takes a certain originality to describe the Nazi era as “Germany’s blighted and momentous 1930s,” to summarize the events of 1933 as Hitler’s “having attained power,” and to assert that Riefenstahl, most of whose work was in its own decade correctly identified as Nazi propaganda, enjoyed “international fame as a film director,” ostensibly like her contemporaries Renoir, Lubitsch, and Flaherty…These films were not simply “tensely romantic.” [Arnold] Fanck’s pop-Wagnerian vehicles for Riefenstahl were no doubt thought of as apolitical when they were made but they can also be seen in retrospect, as Siegfried Kracauer has argued, as an anthology of proto-Nazi sentiments. The mountain climbing in Fanck’s pictures was a visually irresistible metaphor of unlimited aspiration toward the high mystic goal, both beautiful and terrifying, which was later to become concrete in Führerworship.

Chronicling Riefenstahl’s career from the silent era through to the final decades of her life, Veiel’s documentary covers plenty of ground previously trodden by others and, in this sense at least, is thus more of a supplement than a revelation.

Nonetheless, I found his portrait of Riefenstahl deeply fascinating as a character study. This is partly thanks to the voluminous new archival evidence it brings to bear against her longstanding personal narrative. To this end, we are treated to private voicemail messages and recorded conversations between Riefenstahl and Nazi architect Albert Speer, whose advice she actively sought when assembling her memoirs. (Having been convicted at Nuremberg, Speer was released in 1966 and was probably more successful at rehabilitating his image than any other Nazi official.)

By far the most disturbing of these voice messages, however, are those from Riefenstahl’s fans in the West German public who showered her with support in the wake of a famously testy 1970s TV panel (the film leaves this unspoken, but one gets the distinct sense her partial rehabilitation was owed somewhat to the psychological appeal she held for other Germans similarly unable or unwilling to confront their own complicity in the Holocaust or other Nazi atrocities). Also included is unused footage from Triumph of the Will that only makes its director’s assertions of cinematic neutrality look even more dishonest and ridiculous. If Riefenstahl’s self-serving account of her own life was already thoroughly unconvincing, it looks positively outrageous now.

But what struck me most watching Veiel’s documentary was her total inability to keep her own story straight or settle on a coherent narrative of self-justification.