Anti-politics and the English Language

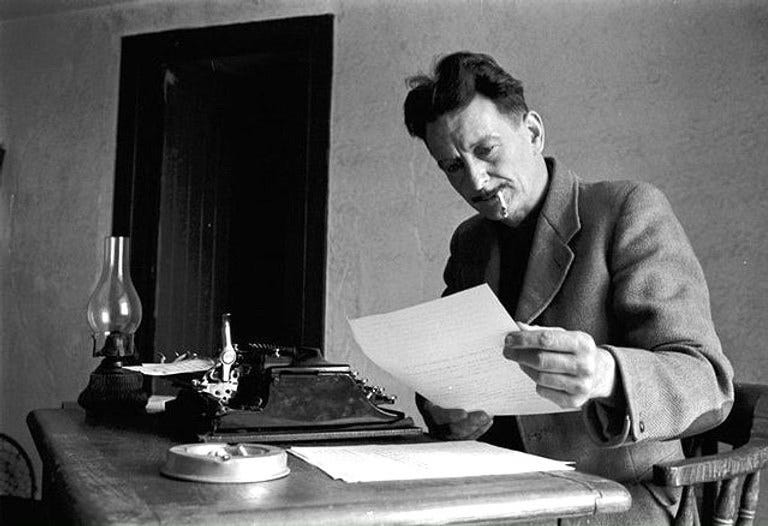

In 1946 George Orwell warned that vagueness and convolution were destroying the English language. Today, writing and speech are plagued by very different problems.

Elsewhere on this site, Corey Robin has this to say about an annoying tic he’s recently noticed in writing and prose:

My latest writing pet peeve: the use of “a kind of” and “a sort of.” I don’t know when I began noticing this writing tic, in myself and in the larger culture, and I don’t know how long it has been around. I’m certain I’ve seen these phrases in writing from as long as a century ago, but it’s all over the place now. I associate it with a sort of—oops, I did it again!—literary affectation that one sees not only on social media but in legacy media as well. Along the lines of Lionel Trilling saying, “Goethe says somewhere...,” but in a tweet, a post, or a piece. It evokes a Jamesian spirit of the ineffable, the not quite, the almost, that liminal space between the is and the is not. It’s meant to suggest a fineness of distinction, I suppose, the subtlety of one’s antenna. But it seems like little more than a cover for an insufficiency of one’s distinctions, a failure of thought, an inability to state as fully as possible what one is thinking or trying to think. I can’t stand it. I’m going to try to stop. Kinda, sorta.

Robin is most definitely onto something here, and the particular tactic of equivocation he’s talking about is really just the tip of the iceberg. In the worst instances, the instinct to qualify and hedge sometimes goes beyond mere evasiveness and effectively puts a cloud of ontological doubt over the author’s own chosen words and concepts.

As I wrote back in May:

There’s a certain genre of left-coded writing that’s rightly derided for its convolution, even meaninglessness. Perhaps the most common hallmark of this style is the incessant bracketing of words in scare quotes, a tactic which can allow the author (or “author”) to assert ideas or concepts while remaining aloof and evasive about what it is they’re actually saying. Sometimes there are random capitalizations as well, or particular sentences are italicized for no discernible reason. In this genre, everything — right down to the very act of writing itself — plays out in linguistic abstraction, and at a convenient remove from anything tangible or concrete.

As far as good prose are concerned, none of this is particularly helpful. Whatever its style, genre, or topic happens to be, writing is usually best when it conveys ideas — even, and perhaps especially, complicated ones — with economy and directness.

This was the main argument of George Orwell’s famous 1946 essay Politics and the English Language, which pilloried the political and academic writing of its day along essentially these lines. The essay is always fun to read because, among other things, Orwell entered an absolutely grating collection of dishonourable mentions into the annals of bad writing. I still find this hard to get my head around, but in the mid-1940s even a distinguished scholar like Harold Laski was somehow content to produce a sentence like this:

I am not, indeed, sure whether it is not true to say that the Milton who once seemed not unlike a seventeenth-century Shelley had not become, out of an experience ever more bitter in each year, more alien (sic) to the founder of that Jesuit sect which nothing could induce him to tolerate.

Orwell saw vagueness and imprecision as the hallmarks of bad prose, but for him they were also the natural allies of ideological insincerity. If bad writing, as he saw it, often trades in staid expressions or dead metaphors that save author and reader alike the bother of actually thinking, propaganda and grandiose rhetoric can do the same thing in more sweeping fashion with entire categories and concepts. As an alternative, Orwell offered a number of general rules for writing, the bulk of which had to do with concision and directness. I don’t think they apply universally (neither did he) but most writers would probably do well to take them seriously even when choosing to ignore them.

****

Like so much in Orwell, Politics and the English Language still gives us plenty to think about, and many of the essay’s complaints still ring perfectly true. Some rhetorical techniques are timeless, and those who want to evade or mislead can still regularly be seen relying on meaningless words or retreating into vacant abstractions. To wit: if a politician tells you they want to “put politics aside and focus on the economy” there’s a good chance their real intention is to give some billionaire a tax cut. And if they begin a sentence with the words “Let me be clear…”, they’re probably getting ready to lie or obfuscate.

Still, in revisiting Orwell’s essay this morning I was struck by a competing thought about the reigning tendencies in language today. Thanks to the incentive structures of social media, and the related imperatives of the attention economy, writing and speech have in many ways only become more direct and concise. This trend, it seems to me, is practically universal. Whether you’re a business looking to advertise, an engagement farm in search of clicks, an institution or bureaucracy doing PR, or just a person with an opinion about something, our oversaturated media environment offers little room for breadth or subtlety. Whatever its tone or purpose, most internet-speak thus defaults to a register of unqualified assertion.

It’s an impulse that’s clearly spilled into our offline vernacular as well, and the upshot is a style of communication that is increasingly unable to accommodate nuance or equivocacy. The vocabulary of qualification (that of shades, gradients, degrees) has seen a consequent drop in value because it by definition works against the kinds of hyperbole and rhetorical maximalism that form the lingua franca of our distracted age.

It’s no accident, I think, that the most powerful figure in the world today is a former reality TV host famous for trafficking in superlatives and putting exclamation marks at the end of sentences even when they don’t belong. For Donald Trump, Joe Biden cannot simply have been a bad president. Instead, he must be the worst president in American history, and the same logic applies when his tenor is positive. Here, for example, is Trump addressing the board of McDonald’s a few weeks ago:

[And we] knocked out Iran nuclear capability and all of the Middle East became a different place. And now we have peace in the Middle East and at the United Nations today, they approved the Board of Peace, which is -- I’m going to chair. And we’re picking the leaders or the heads of the most important nations in the world. I think it will be a board like no other, other than perhaps the McDonald’s board, you have a very good board. You actually have a very good board. But nobody thought a thing like that was -- this just happened today, the Board of Peace. And it’s going to be comprised of myself and leaders of other very important nations and very respected nations. And it’s going to be something I think is going to be very important. It was just approved - it was -- it was just endorsed by the United Nations. It was pretty great. It’s a big thing. I think it’s one of the most important things the United Nations will ever do, actually.

I won’t try to tally all the Trumpian hyperboles in this passage, but I think it makes the point. Bombing Iran, for Trump, must necessarily have implications for the entire Middle East. The UN’s new “Board of Peace” — an Orwellian phrase if ever there was one — must be utterly singular (“a board like no other”) and cannot merely have members or delegates. Instead, it must have the leaders AND heads of the most important AND respected nations in the world who will, in turn, be gathered around a table where he presides as chair. (Not to belabour the point, but let’s also not lose sight of the fact he is saying all this to representatives of a hamburger company.)

Also striking in the speech is the peculiar way Trump’s default to maximalism flattens any sense of scale or proportion. Here and elsewhere, he invariably levels praise and derision in identical terms regardless of the subject or target. Thus, everything from the sugar used in Coca-Cola — which incidentally earned its own digression in Trump’s McDonald’s speech — to a new diplomatic initiative that will supposedly inaugurate a thousand years of peace in Central Asia are similarly perfect and fantastic in every way. Before becoming president, Trump passed the time by hurling epithets at Rosie O’Donnell, litigating his beefs with b-stream gossip columnists on Twitter, and trying to convince Robert Pattinson to break up with Kristen Stewart. Today, this style of flamboyant pettiness remains completely unchanged. Its targets just happen to be powerful Democrats and world leaders.

****

The US president might be an extreme case, but his baroque style of communicating is in many ways an authentic reflection of the zeitgeist. Think clickbait headlines and cloyingly inspirational Facebook posts. Think self-help books with titles like How to Succeed Wildly At Everything While Loving Life And Totally Kicking Ass or articles that deem some trivial comment by an actor or celebrity “everything we needed right now.” Think bird-brained pop culture writing stuffed with needless intensifiers and tweets that go viral by blaring some totally self-evident point in all caps three times in a row. Think comment section flame wars where minor differences of opinion or taste inexplicably devolve into duelling versions of the charge that you, sir, are quite literally Hitler.

In our day, the median register in writing and speech has become so pithy and direct that there must always be a perfectly taut line running from premise to conclusion; a posture of affected certitude even when the context clearly calls for something else. Here, in turn, any sense of scale or proportion is lost because the reflexive dealing in maximums and absolutes has the effect of rendering everything — no matter how weighty or minute — in exactly the same way. Sixty years ago, a person who used the word “epic” in a sentence was probably talking about high romance or Homeric poetry. Today, they might easily be describing anything from bacon to nuclear war.

These trends inevitably press down on writers themselves. As someone who has spent the past decade writing for a living, I have often (though not always) found there to be an inverse relationship between what’s interesting and what gets noticed. If an argument cannot be neatly distilled into a simple, declarative title or headline it is at a considerable disadvantage. Ergo, it becomes increasingly tempting not just to package ideas in the most blandly explicit terms but to formulate them from the outset with that end in mind.

All this has implications not only for how we speak and write but also for how we think, debate, and argue. Orwell again:

It is clear that the decline of a language must ultimately have political and economic causes: it is not due simply to the bad influence of this or that individual writer. But an effect can become a cause, reinforcing the original cause and producing the same effect in an intensified form, and so on indefinitely. A man may take to drink because he feels himself to be a failure, and then fail all the more completely because he drinks. It is rather the same thing that is happening to the English language. It becomes ugly and inaccurate because our thoughts are foolish, but the slovenliness of our language makes it easier for us to have foolish thoughts.

****

Orwell’s observation still applies, but I think the character of our own slovenliness is largely of a different kind. The decadence in language we confront today has less to do with imprecision, clunky symbolism, or the smuggling of unexamined dogmas into prose through passive voice or hifalutin metaphor. Instead, we are bludgeoned from all sides by writing and speech that is paradoxically too direct and efficient — a style made vacant, bloodless, and garish not by its convolution or reliance on opaque jargon but by its flatness, didacticism, and droning certainty.

If some of Orwell’s complaints now seem out of date, it’s mainly down to the passage of time and a number of wider shifts in the nature of discourse as a whole. In 1946, the public square was heavily populated by academics and ideologically-motivated pamphleteers. Representatives of each group abused language in different ways — the lazy scholar leaned on latinate phrases and pretentious diction, the unthinking ideologue on crude slogans — but the effect was often the same.

Insofar as a public square still exists in the 21st century, its most influential actors are instead people who think, write, and speak instrumentally for a living: the likes of consultants, marketers, communications and PR professionals, political spin doctors, branding specialists, and a broad swathe of others who might publicly call themselves “influencers” or “content creators” without even a hint of irony. Whatever else, obscurantism is clearly not the problem here.

The discursive ecosystem itself, needless to say, is very different too: its form being primarily digital; its incentive structures more thoroughly monetized; its defining features being inattention and excess. Orwell’s Europe was a place of grand narratives and mass political parties. Today, instead, there is a climate of widespread social atomization and a generalized absence of common narratives of any kind.

Still, our problem expresses itself in much the same way: through a series of self-reinforcing tics, enforced patterns, and bad habits that make language less beautiful and writing less able to render the full spectrum of human feeling and experience. Inevitably, this has more than just aesthetic consequences. Among other things, it contorts our moral lexicon into crude, Manichean binaries and in turn risks neutralizing politics because deliberative democracy needs pluralism to function. Criticism and culture writing are similarly made worse because most songs, books, or movies worth discussing are almost never, simply, good or bad.

Communicating ideas effectively or elegantly requires time, breath, and attention, all of which are now scarce commodities for writers and audiences alike. It also requires a firm sense of scale and proportion, and a willingness to accommodate ambiguity even when the lack of it might carry greater rhetorical power. The liminal space between the is and the is not, as Robin puts it, can be used cynically by individuals who want to be aloof or evasive. But when large numbers of people are involved, as they are bound to be in politics and culture, it is a vital prerequisite for any public discourse worthy of the name — and for any form of writing with loftier ambitions than those of an advertisement or instruction manual.

Grateful for this thoughtful essay, Luke. Reading the diaries of Victor Klemperer, I remember that the German-Jewish philologist, who was well-attuned to Nazi propaganda, repeatedly noted the impact of hyperbolic US advertising language on the German media in the 1930s. The exaggerations, short-hand expressions, exclamation-point-ridden prose and simplistic forms of expression became more commonplace as the war continued, and the Wehrmacht faltered. Klemperer’s book Lingua Tertii Imperii (LTI) makes a more extended argument about the same topic. Geremie

I’ve noticed a lot of these peculiarities myself. The primacy of certainty and authorial confidence is interesting in a time of collapsing institutional faith. It feels at times like a defense mechanism. In my personal experience, things have become so strange that I can’t be sure whether or not I’m dreaming, or if any of this is real at all. And yet sometimes I’ll catch myself speaking with confidence about a thing I don’t completely understand.